According to FactSet, S&P 500 earnings will drop roughly 8.3% in the first quarter. That’ll mark the fourth consecutive quarter of declines in corporate profits-per-share. Why might that matter? There are only two occasions over the previous two decades where earnings contractions lasted longer. In both instances, the U.S. economy experienced a recession; in both instances, the S&P 500 lost HALF of its value.

Does the current earnings malaise mean that history will repeat itself? No. On the other hand, there are always reasons for a slump in profits. Those who ignored the tech sector’s warnings in 2000 witnessed their portfolios disintegrate. Similarly, those who pushed aside the financial sector’s admonitions in 2008 experienced life-altering losses.

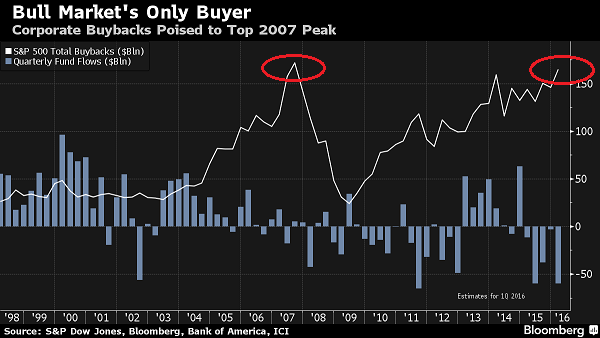

There is another reason why the contraction in corporate profits are a troublesome omen. Historically, declining earnings weigh on corporate confidence with respect to buying back shares. Extended periods of earnings contractions have led companies to sharply reduce their acquisition of shares in the past. The average pace of share reduction was a peak-to-valley slowdown of 62 percent. It follows that with corporations serving as the only significant buyer of stock at this moment – with retail investors, institutional investors, hedge funds, pensions as well as mutual fund managers participating as “net sellers” – we may be staring at the peak in the corporate buyback cycle.

The bullish counter-argument to the notion that companies may slash their buyback activity is the new corporate bond buying program by the European Central Bank (ECB). Specifically, the ECB’s willingness to buy non-sovereign debt – their eagerness to purchase company obligations in addition to country obligations – has the effect of tightening corporate credit spreads. In English, please? The cost of corporate borrowing around the world should move even lower. And if it does so, why… how can companies resist the urge to borrow more money to buy back more shares?

Leave A Comment