According to economic theory, one of the most promising ways in which monetary policy might be able to stimulate an economy in which the nominal interest rate has reached zero is to promise to follow a different policy rule once interest rates are again positive. A commitment to more stimulus and inflation in the future regime could in principle influence expectations and actions of people in the economy today, and thereby offer a means by which the central bank could help an economy recover from the zero lower bound. But as a practical matter, how does the Fed communicate to the public at of something it intends to do at some future date?

What the Fed actually did was to issue the following statement on August 9, 2011:

The Committee currently anticipates that economic conditions–including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run–are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.

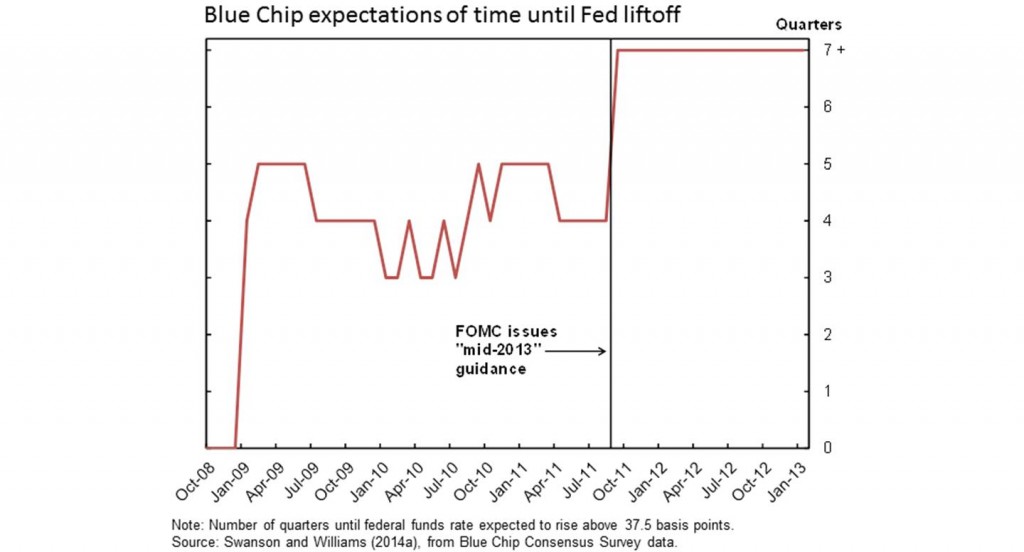

The key departure from previous statements was the link to a calendar date one year and three quarters ahead. What did market participants make of this announcement? Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President John Williams last week described the August 2011 statement as a “sledgehammer” that very effectively delivered the Fed’s message. Williams noted for example that the Blue Chip consensus estimate of how long it would be before the Fed started raising interest rates jumped from 1 year before the statement to 1-3/4 years after the statement.

Figure 1. Source: John Williams.

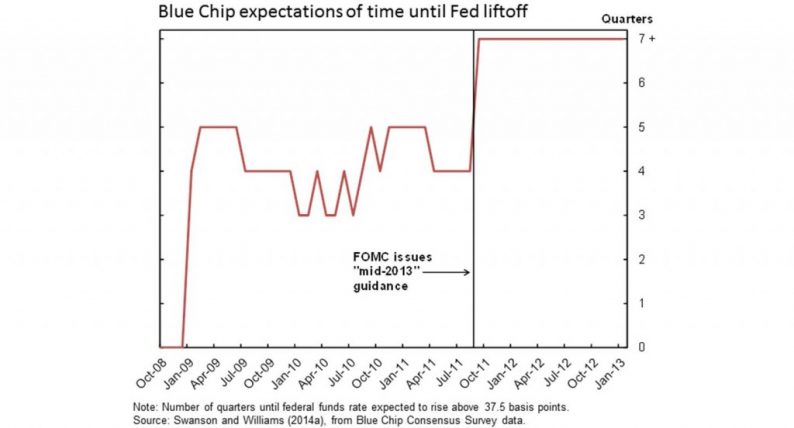

Such “forward guidance” had the potential to start influencing economic activity the minute that the statement was issued in August of 2011. If markets were persuaded that the Fed was going to keep rates low for a longer period, longer term interest rates should fall on the news. And indeed, the yield on a 5-year U.S. Treasury bond fell by 20 basis points on the day the Fed released the statement. Lower interest rates on longer term borrowing could help to increase spending right away.

Figure 2. Yield on 5-year Treasury bond as of close of business each day, with values before and after the August FOMC statement highlighted with black and red lines, respectively.

But committing today to a future decision is problematic in both theory and practice. The Fed may say at time t that it is going to take a certain action at some future date t+h, but when the date t+h finally arrives, what prevents the Fed from embarking on a new plan rather than the one it announced at date t? If the Fed had wanted to raise rates at the end of 2012, would the August 2011 statement somehow have prevented it from doing so? A 2012 paper by Campbell, Evans, Fisher, and Justiniano drew an analogy to the account of the legendary Greek King Odysseus, who instructed his crew to bind him to the mast of his ship so that he would be denied the temptation of steering the ship toward the enticing songs of the Sirens. By announcing in August 2011 that it did not intend to raise rates over the next 7 quarters, the Fed was intentionally making it more difficult for it to deviate from that announced course.

Leave A Comment