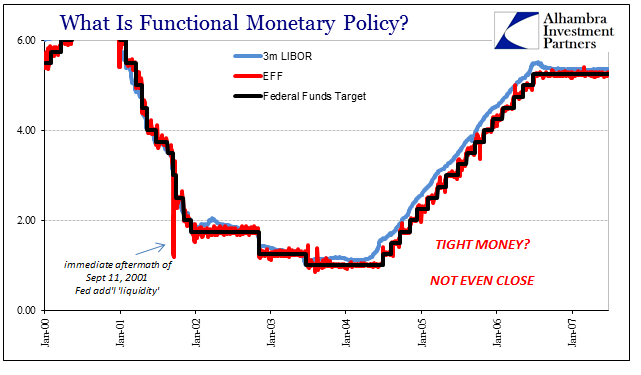

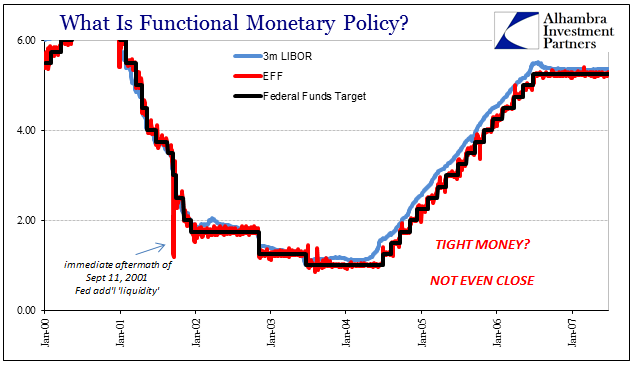

The textbook says that whenever the central bank raises its policy rate that means tightening. Actual experience over more than just this last lost decade demonstrates that at the very least it is much more complicated than that. There is far more evidence of monetary policy being nothing more than a response, as that reverse condition can absolutely be established by global monetary behavior time and again. Alan Greenspan “tightened” from June 2004 forward to no effect, and then Ben Bernanke “accommodated” in perfectly equivalent fashion from September 2007 forward, likewise to no effect.

In the past month and three days we have run into the same sort of contradiction. The FOMC voted in mid-March to “raise rates”, but all it really did was increase the upper and lower boundaries for the federal funds rate. Unlike the pre-crisis era, there is today much more looseness as money market hierarchy was obliterated (not by regulations or bank reserves) by the paradigm shift of bank balance sheet behavior (risk vs. reward). Federal funds are completely irrelevant, but for practical purposes they might as well be. Therefore, as little as a “rate hike” might have meant in 2005 or 2006, it means even less in 2017.

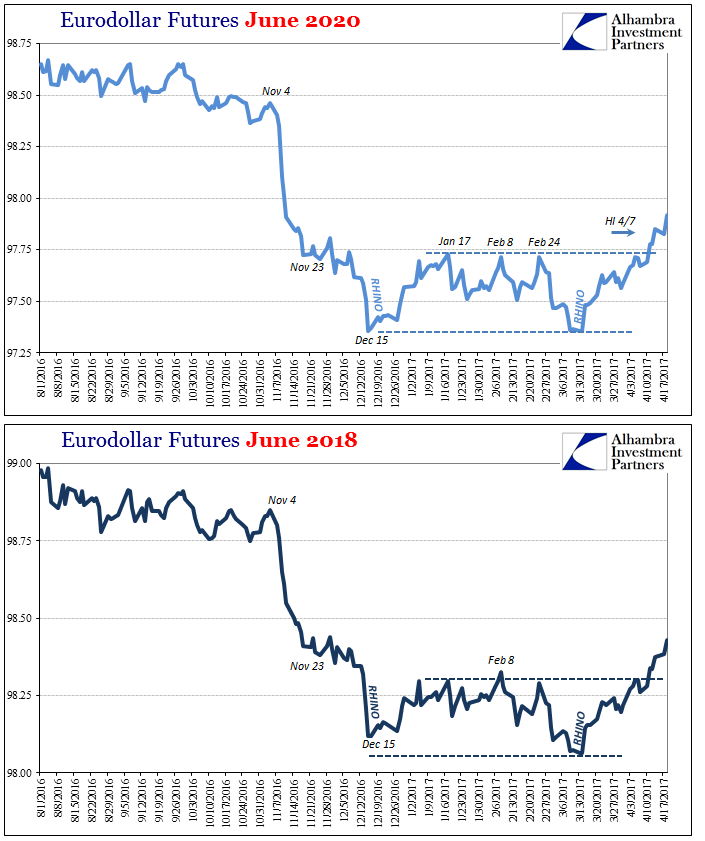

That doesn’t necessarily leave, however, monetary policy changes as completely benign and totally extraneous; it merely means that whatever effects it might create aren’t likely to be what is described of them. With rates falling and the eurodollar curve collapsing again, we know without fail that “rate hikes” deserve fully the quotation marks. But since this latest trend now undoing the whole of the range of the past few months dates back to the FOMC vote exactly, we are forced to consider just how the Fed (if not China and CNY) might have played a role in establishing it no matter how counterintuitive it might be in relation to the textbook approach.

Leave A Comment