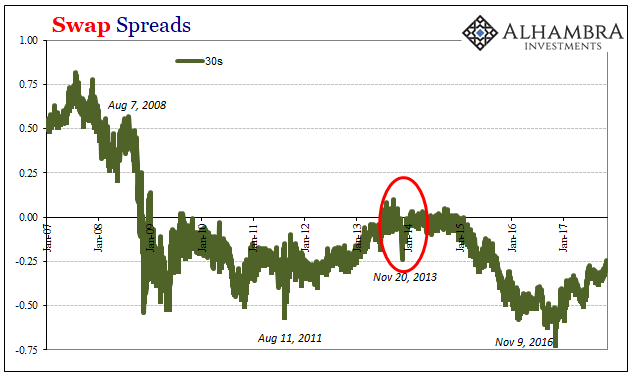

For quite a long time I obsessed over November 20, 2013. It was a day that for the vast majority of humanity was like any other, nothing too far out of normal and certainly nothing that would seem to mark it for remembrance. But in my realm of yield curves and interest rate swaps, the things that tell us a little something about the eurodollar’s world, the one we all actually live in, November 20 was an earthquake or a volcanic eruption.

For one, swap spreads collapsed – by a lot. For a single day or two days, a move like that wasn’t unheard of, only that big countermoves to trend were usually timed to surprises in Fed announcements. The 30-year swap spread, the difference between the quoted interest rate swap rate from ICE and the same maturity US Treasury yield, had sunk from -9 bps on Monday the 18th to -13 bps Tuesday the 19th and finally all the way to -24 bps that weird Wednesday.

What made it all the more intriguing was that for several months up to that point swap spreads were decompressing in what sure seemed (to convention) like reflation. A negative swap spread is an assault on basic finance, something that wasn’t supposed to be possible (getting paid less on the fixed leg of an interest rate swap than a similar UST suggests on the surface the market believes private largely financial counterparties are less risky than the United States Treasury; that’s nonsense, of course, where instead a negative swap spread only tells us that something is wrong on the inside of the monetary system; i.e., balance sheet capacity to address what should easily fall under covered interest parity). Getting back to a zero 30-year spread for the first time since late 2008 was widely hailed as one of those round-number points of significance (that are still serialized today).

It wasn’t just IRS swap prices that registered the rumble, either. The UST curve at the 5s10s which had been moving sharply steeper abruptly reversed (though it would be some time before that reversal was far enough along to be clearly indicated as such). Most people tend to pay attention to the 2s10s and only for the possibility of inversion, but it’s the 5s10s (in between) where everything that really matters gets sorted out – including some very direct relationships with other monetary spaces like interest rate swaps.

Leave A Comment