That’s the title of a paper with David Greenlaw, Managing Director of Morgan Stanley, Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, and Kenneth West, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin, which we presented at the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum annual conference in New York on Friday.

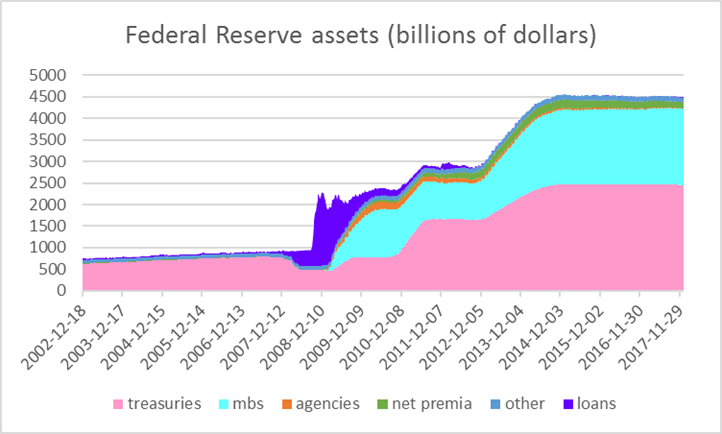

Assets held by the Federal Reserve quintupled between 2007 and 2014. The initial phase of this expansion took the form of emergency lending in the fall of 2008, shown in purple in the graph below. These doubled the Fed’s balance sheet within the space of a few months, but were subsequently repaid and are now off the books. Our paper does not discuss the efficacy of the Fed’s lending programs.

Federal Reserve assets, Dec 18, 2002 to Jan 3, 2018. Wednesday values in billions of dollars. Treasuries: U.S. Treasury securities held outright. MBS: Mortgage-backed securities held outright. Agencies: Federal agency debt securities held outright. Net premia: unamortized premia minus unamortized discounts. Other: sum of float, other Federal Reserve assets, foreign currency denominated assets, gold, Treasury currency, and special drawing rights. Loans: sum of loans, net portfolio holdings of Commercial Paper Funding Facility LLC, Maiden Lane I, II, and III, net portfolio holdings of TALF LLC, repurchase agreements, preferred interests in AIA Aurora LLC and ALICO Holdings LLC, central bank liquidity swaps, and term auction credit. Data source: Federal Reserve H41 archive. Source: paper.

Our focus is instead on the steady purchases of Treasury securities (in pink) and mortgage-backed securities (in turquoise) carried out in three separate phases popularly referred to as QE1, QE2, and QE3. As Ben Bernanke put it just before he stepped down as Chair of the Federal Reserve, “the problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.” In standard macro-finance models, these should not have had any effect on interest rates or economic activity (see for example Eggertson and Woodford, 2003). More refined models imply potential effects from altering the supply of publicly held Treasury securities, coming from factors such as nonpecuniary benefits some institutions may derive from holding Treasury securities (Woodford, 2012) or preferences or restrictions on the kinds of securities different institutions hold (Chen, Curdia and Ferrero, 2012; Greenwood and Vayanos, 2014). Another possibility is that large Fed holdings of Treasury securities implicitly or explicitly commit the Fed or the Treasury to alternative future policy (Hamilton and Wu, 2012; Eggertsson and Proulx, 2016).

Leave A Comment