You can understand to some small degree economists’ collective confusion about inflation. They believe in wage dynamics, where a recession through mass layoffs creates slack and thus depresses wages. The recovery in a period of robust growth re-employs those unfortunate workers, and after enough time when that slack is reduced or even eliminated wages accelerate again (increased competition for labor). As they do, businesses are forced to raise prices to maintain profits, while workers as consumers buy more stuff and can afford those price increases.

It is the virtuous orthodox circle that they always seek in the aftermath of any business cycle. In modeling this one, though, they believed because of the harshness of the downside as well as the clear sluggishness (by QE3 in 2012) in recovery it would take several years more in order for slack to be sufficiently dissolved.

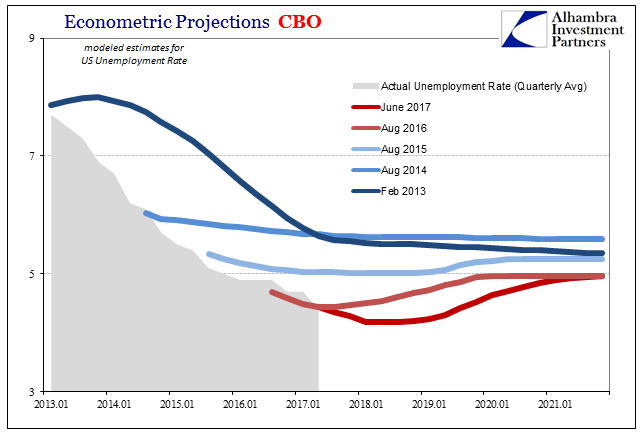

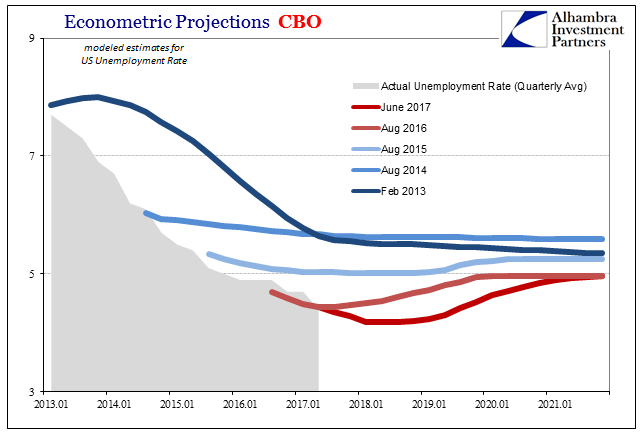

Since we are not privy to Federal Reserve models, I use instead the CBO’s; not because I believe them any more accurate, or accurate at all, simply because in all likelihood they are very close to the Fed’s.

In the CBO’s February 2013 projections, those released just after QE4 began, the unemployment rate wasn’t expected to fall below 6% until this year. That would have matched the slow rate of growth then being observed throughout the US (and global) economy.

Instead, the unemployment rate practically collapsed. It broke below 6% in late 2014, more than two years early. In 2016, it fell below 5%, which up until that time the CBO expected would have been appreciably less than “full employment.” By this view of the economy, there is every reason to suspect wage acceleration and then broad inflation (according to the orthodox inflation framework noted above).

And that is exactly what the CBO forecasts for worker compensation were predicting. But as the actual unemployment rate fell below whatever level of prefigured “full employment” at each point without triggering rapid wage growth, the models have been forced to reconsider what might be “full employment.” In doing so, the impact on expected wages is both a delay and reduction in that point.

Leave A Comment