After Fed Chair Powell’s latest FOMC presentation, and also following his speech yesterday, the general market consensus was that the Fed is on auto-pilot for the conceivable future, at least until something changes. But what could make the FOMC speed up the pace of tightening? What would make it pause? And how will the Committee know when it’s done? While comments from Chairman Powell offered some answers to these questions, Goldman has conducted an analysis on the FOMC’s decisions to accelerate, pause, or conclude the 1994-1995, 1999-2000, and 2004-2006 hiking cycles offer additional clues.

First, a quick reminder of what Powell said in his press conference following the September FOMC meeting: first, Powell offered some guidance on what it would take for the Fed to deviate from its projected policy path, when he said that potential triggers for a pause include either a “significant and lasting correction in financial markets or a slowing down in the economy that’s inconsistent with our forecast.” The main trigger for raising rates more quickly, Powell said, would be if “inflation surprises to the upside.”

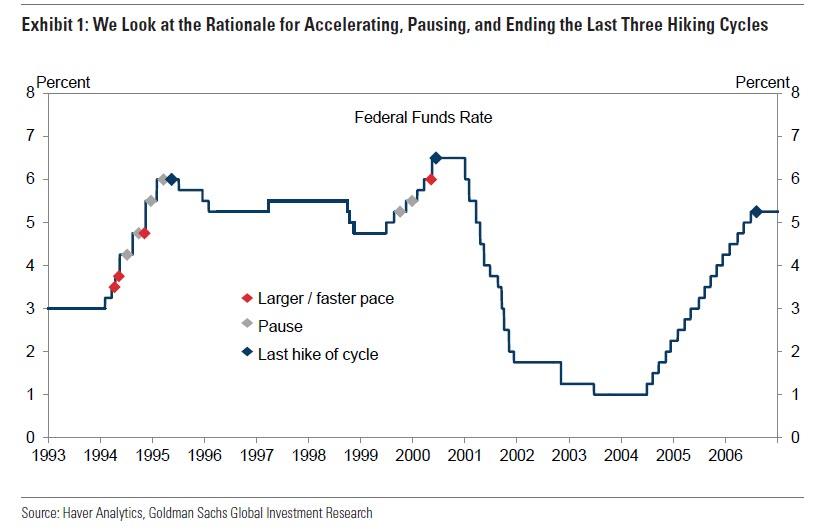

So far so good; however for some additional clues about what the Fed would need to see to accelerate, pause, or conclude its hiking cycle, Goldman looked back at the last three hiking cycles, and identified moments where the Fed accelerated, temporarily paused, or concluded its rate hikes during the last three (1994-1995, 1999-2000, and 2004-2006) hiking cycles, as shown in the chart below. Goldman then investigates the rationale for these policy decisions below by looking back at the statements, minutes, and transcripts from FOMC meetings at the time.

1. Accelerating the hiking cycle

While hardly a realistic outcome this time around absent a surge in average hourly income above 3.0%, the 1994-1995 hiking cycle provides one example where the Fed picked up the frequency of rate hikes (an intermeeting hike in April 1994) and two where it increased the size of its rate hikes (50bp in May and 75bp in November 1994).

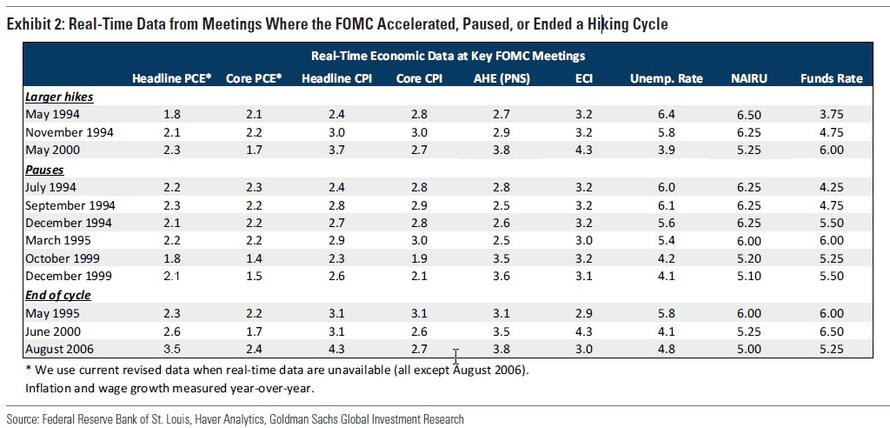

According to Goldman, transcripts from FOMC meetings at the time indicate that the Committee worried that strong growth would eventually raise inflationary pressures and responded with a faster pace of tightening in order to avoid falling behind the curve and secure its inflation-fighting credibility. Exhibit 2 shows real-time economic data at the time of these meetings.

Here are Goldman’s thought on the rate hike acceleration triggers:

At the end of the 1999-2000 hiking cycle, the FOMC delivered a larger 50bp hike in May 2000. Core inflation was around 2%, but growth was extremely strong and participants were concerned about a dip in the unemployment rate to 3.9%, a 30-year low, and an acceleration in wage growth that former Chairman Greenspan considered “unambiguous” and Governor Meyer saw as a clear inflection point.

Leave A Comment