Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans got some attention recently with the following statement:

In a world of global competition and new technology, I think competition is coming from new places. New partners are choosing to merge and sort of changing the marketplace and [bringing] more competitive pressures on price margins…If that’s the case, and I think that’s just speculative at this point, then it means that we need even more accommodation to get inflation up.

Here are some of the data that might support such a statement. The existence of a Phillips Curve is one of the Fed’s core assumptions: as unemployment gets lower, the inflation rate should pick up. We’ve seen a huge drop in unemployment over the last six years. And in response, inflation did … pretty much nothing. It sure looks like other factors — maybe changes in competitive structure, maybe something else– are having a bigger influence on inflation than is the unemployment rate at the moment.

Inflation rate measured as year-over-year percent change in the implicit price deflator on personal consumption expenditures (second quarter to second quarter for 2010-2016, first quarter to first quarter for 2017), and unemployment rate (June of each year for 2010-2016, May for 2017).

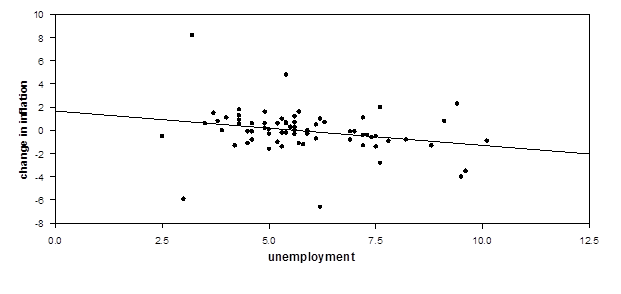

But to that I’d add this– there’s really nothing new about the claim that other factors have a bigger influence on inflation than the unemployment rate. Here for example is a scatter plot going back to 1949 of the year-over-year change in inflation against the unemployment rate. I’ve drawn the regression line, as economists like to do, to help your imagination see the modest negative relation that holds in the data. But it is indeed modest, with an R2 of only 6%.

Annual data, 1949-2017. Vertical axis: year-over-year change in the inflation rate. Horizontal axis: unemployment.

Of course, economists have been teaching for a couple of generations that the Phillips Curve shifts over time due to changes in expected inflation. I’ve actually already incorporated a quick and dirty fix for this in the figure above by measuring the difference between this year’s and last year’s inflation on the vertical axis. If people expect this year’s inflation to be the same as last year, the result (as in Charles Jones’s macroeconomics textbook) is a Phillips Curve adjusted for expectations.

Leave A Comment