<< Read More: Not All Swaps Are Created Equal; Part 1 (Eurodollar University)

The real clue as to what was going on monetarily was provided in early 2008 not by a Federal Reserve statement about some new program it was hastily putting together (except by proxy of what it meant for conditions in private wholesale markets that the Fed thought it necessary to hurriedly arrange some new liquidity program, of which there were several). It was instead given to us by AIG deep within the notes of its 2007 annual report.

Approximately $379 billion of the $527 billion in notional exposure on AIGFP’s super senior credit default swap portfolio as of December 31, 2007 were written to facilitate regulatory capital relief for financial institutions primarily in Europe.

There are two vitally important terms contained within that short passage. The first is “primarily in Europe”, suggesting why it was that the ECB made first contact with the Fed for dollar swaps all the way back in 2007. Its banks were at the center of all this, though to be proper we need to specify that banks located within Europe were not necessarily European. By that I mean their business was global, and therefore “dollar” rather than strictly euro.

For monetary policy, the issue was to whom these banks belonged. They were a huge part of the global dollar, yet they were European (or Japanese). The Fed’s bureaucratic interests placed exclusive emphasis on geography, not the whole currency system (meaning what it was and is these offshore entities did with and among each other all in the name of dollars). Thus, the US central bank chose instead swaps with other central banks like the ECB so that those other central banks would be responsible for their own.

It was a colossal mistake; seeing institutions by national definitions had the effect of obscuring vital dimensions. The dollar, or “dollar”, was broken, not specific banks in Europe or America.

The second phrase is everything about the mature eurodollar system, largely because it shows us with specificity what that system had become – balance sheet capacity that was traded and provided by outside parties and every bit liquidity as whatever else was on the liability side. The idea of “regulatory capital relief” isn’t particularly dense, though it may seem that way especially attached to the practice of credit default swaps (or interest rate swaps, etc.).

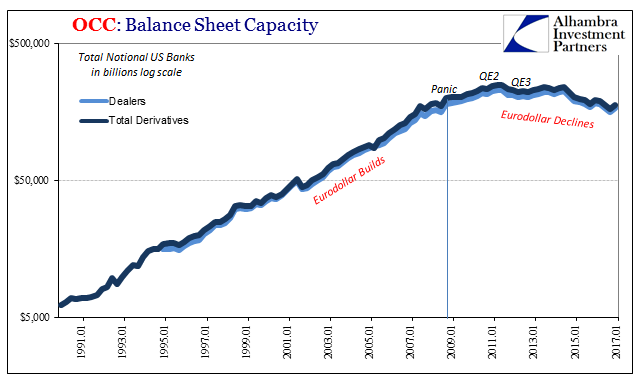

What the Fed wished to swap could not come even close to replacing what banks had been getting swapped from the rest of the private system. What follows in only one of those dimensions, a very important one.

The goal of any financial institution has always been to expand its activities as far as it possibly can. In days long gone, that meant deposits of actual money sitting in one form or another in its vaults (money multiplier). In the latter 20th century, it came to mean something very different. Multipliers still exist, but they have evolved and have been formalized. The concept of Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA), or other balance sheet parameters (I won’t get into them today), is really that leverage in another form (regulatory capital relief).

The Basel rules governed the way in which capital ratios were achieved. They allowed for this sort of accounting, meaning that when first adopted it was thought that any bank holding a risky asset should not be penalized with a reduced capital ratio if it was to pair that risky asset with some sort of guarantee. Originally conceived as a GSE contract for a mortgage bond, the definition of what qualified in this sense was slowly (and greatly) expanded over the decades.

Leave A Comment