Data Interpretation Problems

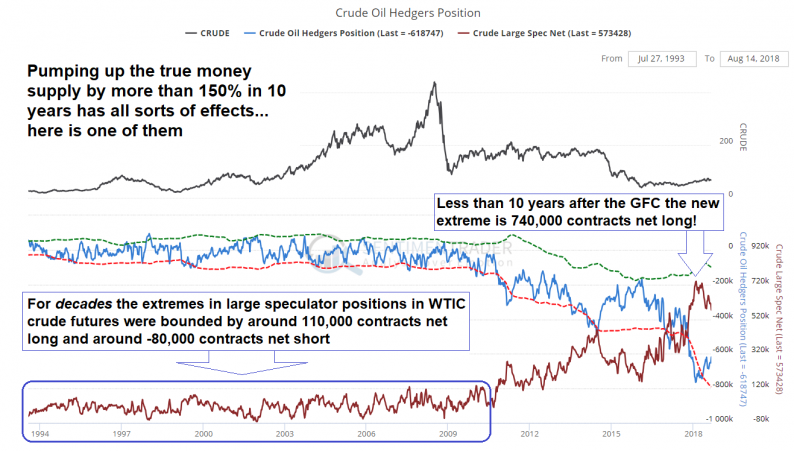

Oddly enough, these days it has become more difficult to interpret positioning data. We get more granular data than before, such as e.g. the disaggregated commitments of traders reports (CoT – even if they are still released with a three-day delay), but at the same time, the goal posts in futures markets have shifted greatly. Former extremes in positioning have been left in the dust with the advent of QE (and the associated desperate “hunt for yield”) and the adoption of large-scale systematic trading. Here is a glaring example illustrating the point:

Speculator net positions in crude oil futures: after decades in which net long positions rarely exceeded 100,000 contracts, a new post-GFC era record has been set in the speculative position at 740,000 contracts net long in early February 2018.

Just because there is more money to go around, there is not more intelligence to guide it, to paraphrase Kenneth Galbraith (a man we otherwise disagree with on almost everything, but this quote is hitting the nail on the head). Then again, we also disagree with the often heard glib assertion that speculators represent the “dumb money”.

In fact, this is demonstrably untrue. For the most part, they are simply trend followers and as such will be correct as long as a trend is in place. They are often grievously wrong near turning points, but not always (or rather, not all of them).

In fact, since the goal posts with respect to what represents an extreme position have shifted to such a great extent in the past decade (in many cases we have yet to establish where the new limits actually are), it is necessary to look for other signposts when trying to interpret the data.

Consider for instance that speculators are not a monolithic group. Some of them are presumably smarter than others, and that should be visible in the data.

That is indeed often the case. We have for example seen clear divergences between prices and the net speculative position at the peaks in crude oil in 2008 and gold and silver in 2011. In other words, a number of speculative longs quietly made their exit from these markets in the weeks before prices peaked.

In 2007 and 2008 speculators correctly concluded that despite official reassurances to the contrary, the housing bust was not “contained” and amassed a large net short position in stock index futures. It was the only occasion we know of when they actually managed to enter a large net short position before the market concerned tanked.

Leave A Comment