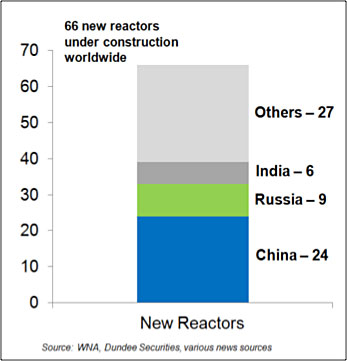

A Grand Canyon of supply deficit is opening up in the uranium markets, with 66 nuclear reactors under construction globally and more restarting in Japan. As Russia and China shore up their supply chains in Kazakhstan and elsewhere, the rest of the world could be scrambling for new sources to keep the lights on. In this interview with The Energy Report, Thomas Drolet, head of Drolet & Associates Energy Services, illuminates junior companies in the Athabasca Basin, southern Alberta and South America that could be strategic sources for countries shoring up domestic supply and for majors that need replacement resources.

The Energy Report: We have heard for years that Japan could be restarting its reactors any time. Is it really happening now?

Thomas Drolet: It is happening; one has just restarted. The intelligence I have gathered from my visits and telephone conferences with Japanese utility people since the Fukushima-Daiichi accident indicates that the restart will be measured, formal and slow. Only 25 of the original 54 reactors will eventually be restarted, in my opinion. The reasons are varied, but include local opposition, proximity to fault lines, regulatory barriers and excessive capital reinvestment needs.

TER: Once they are restarted, how long will it take to work through Japan’s uranium supply backlog?

TD: Utilities—and Japanese utilities are no different than North American, European or Canadian utilities—prefer to buy in the long-term markets. They usually buy somewhere between two and five years’ forward supply. That has left the nine Japanese utilities that have nuclear reactors on their systems stockpiling inventory to fulfill long-term contracts. A few of those utilities paid a penalty to get out of the contracts. But the majority stuck with them, so they do have a lot of inventory on hand.

An average utility that restarts four reactors would burn through excess uranium inventory in about five to seven years. Some reactors will start sooner than the average of the 25, and work through supplies faster, but some will take longer.

TER: In the meantime, how much of an impact can Chinese and Indian nuclear construction have on demand in the uranium market?

TD: Several hundred reactors are being planned or are under construction in China, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Argentina and the United Arab Emirates. That doesn’t include the smaller reactor business in places like Turkey, Jordan, Bulgaria, Bangladesh and Vietnam. That means a Grand Canyon of a deficit in supply from known sources—approximately 30-35 million pounds per year (30-35 Mlbs/year) in what is currently a 155 + Mlbs/year market—will open up by 2020-2022. The way in which the deficit gets filled is going to be a complex process.

TER: If it takes decades to develop a uranium resource, that puts the focus on the junior space, where we have seen a flurry of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) lately. Is that a good sign for uranium mining equity prices for the rest of this year?

TD: First, we have to get through this doldrums period of oversupply over the next few years. We have the big existing suppliers right now in Kazakhstan, in Canada— AREVA SA (AREVA:EPA) (ARVCF), Cameco Corp. (CCO:TSX; CCJ:NYSE) and Denison Mines Corp. (DML:TSX; DNN:NYSE.MKT)—and in Australia. Some smaller in situ recovery (ISR) suppliers work the U.S. and Australia, but that is not going to be enough to fill the approaching canyon. All of this current supply is going to be gobbled up by U.S., European, Chinese, Canadian and Indian users. We’re going to have to look for new supplies from Canada, South America, Europe, the U.S. and Africa.

Leave A Comment