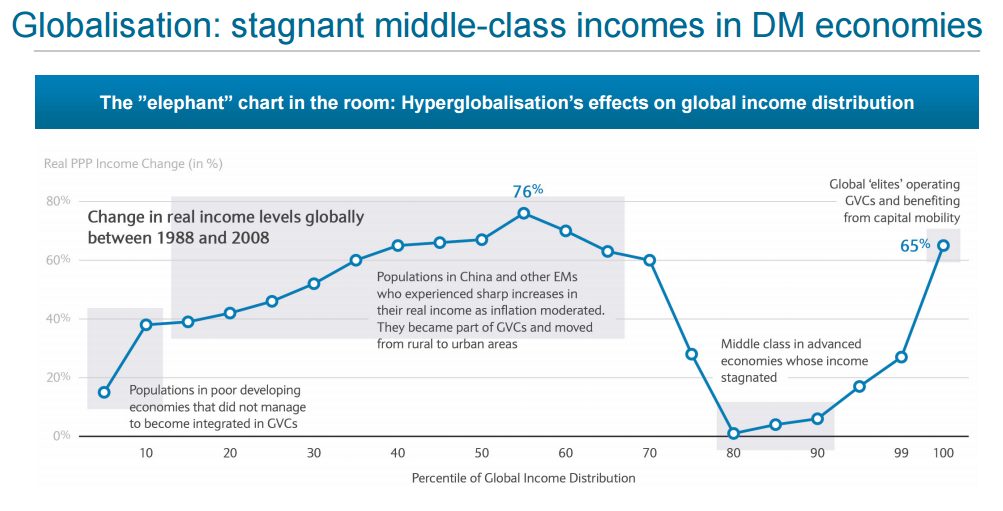

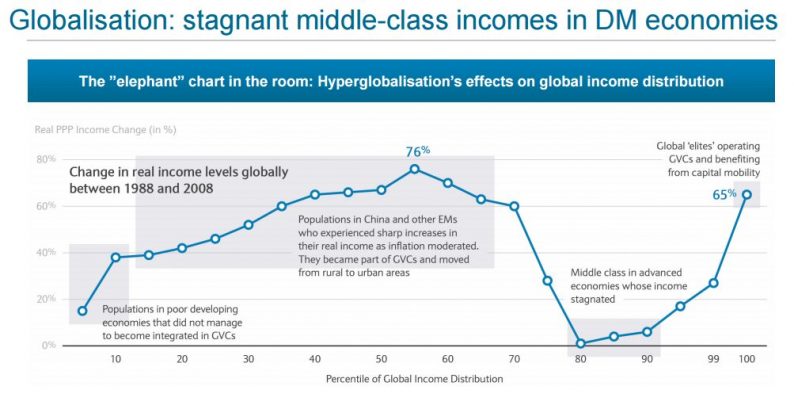

How does one explain the current political divide? In part, this is done by looking at winners and losers in the process of globalization, a recent Barclays report noted. “The middle class in advanced economies whose income stagnated.” In fact, those that “voted for Trump” have seen the sharp end of the sword, while “global elites” who benefit from capital mobility have flourished. While this is the headline that has ushered in a wave of populism across the developed world, there is a bright side to trade theory and benefits will accrue all, Barclays researcher Christian Keller reassures that in this age of hyperglobalization this too shall pass.

The history of globalization

“Trade openness” has is bumping up near all-time highs, with the NBER Macrohistory Database, cited in a Barclays report, pointing to a long history of up and down acceptance of the key concept behind trade.

There was the “first wave of globalization,” from roughly 1875 until near the Great Depression, when exports and imports as a percentage of trade topped out near 38.7, only to find a low near 7.5 near the end of the Second World War and shortly following the Bretton Woods trade accord.

The second wave of globalization started to take off with the advancement of the SWIFT system for global payment processing and the advent of the personal computer, leading to the current phase of Hyperglobalization. This era is marked by global communications tools such as the world wide web and trade agreements such as NAFTA, that led to a reduction in certain manufacturing employment but growth in other job segments.

At the center of the current global value chain are banks providing capital and multi-national corporations utilizing technology and know-how across borders as if they didn’t exist.

But there is trouble in paradise, as “liberal globalization policies are now being questioned.”

Leave A Comment