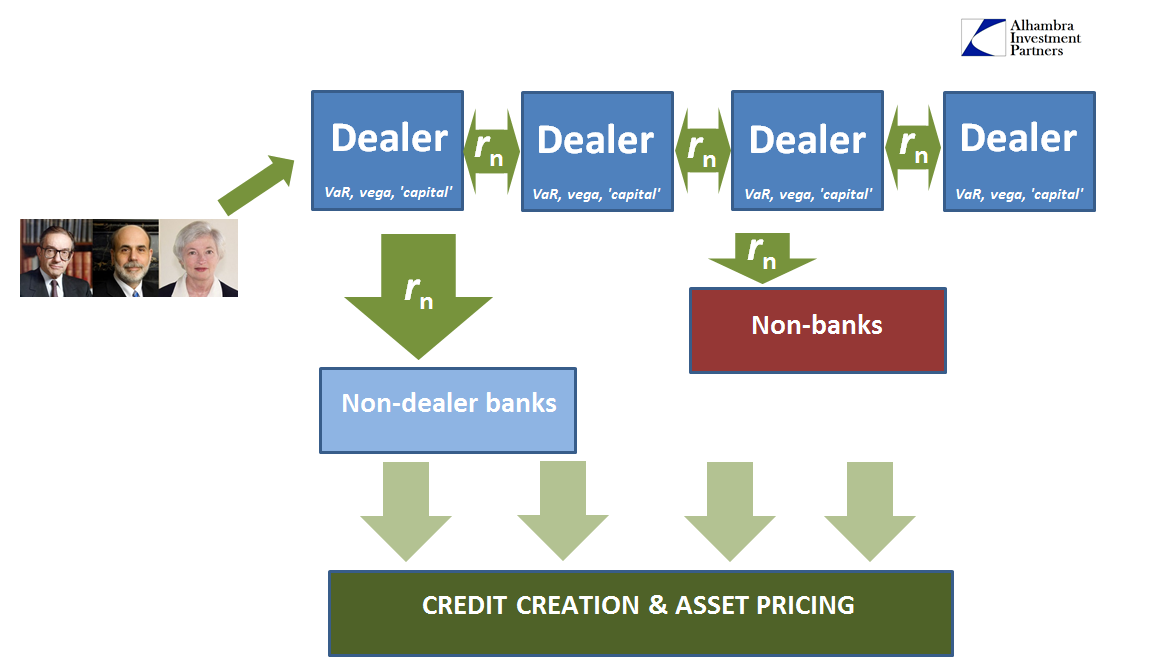

The whole monetary issue as it pertains to the eurodollar system can be succinctly summed up as balance sheet capacity. In pure monetary terms, that is an enormous distinction. What counts as money is not what almost everyone still thinks it is, though those view should have been shifted almost a decade ago in August 2007. Money is instead “money”, where all the various forms of those bank balance sheets become the conditions that drive either monetary growth or contraction. Indeed, it is in many ways impossible now to separate money from credit, a further complication that has only rarely been considered.

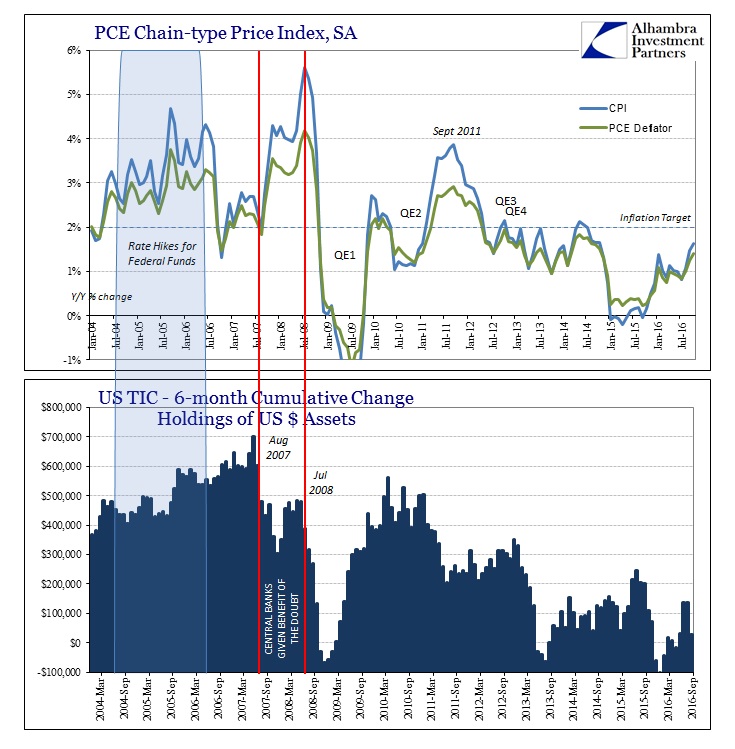

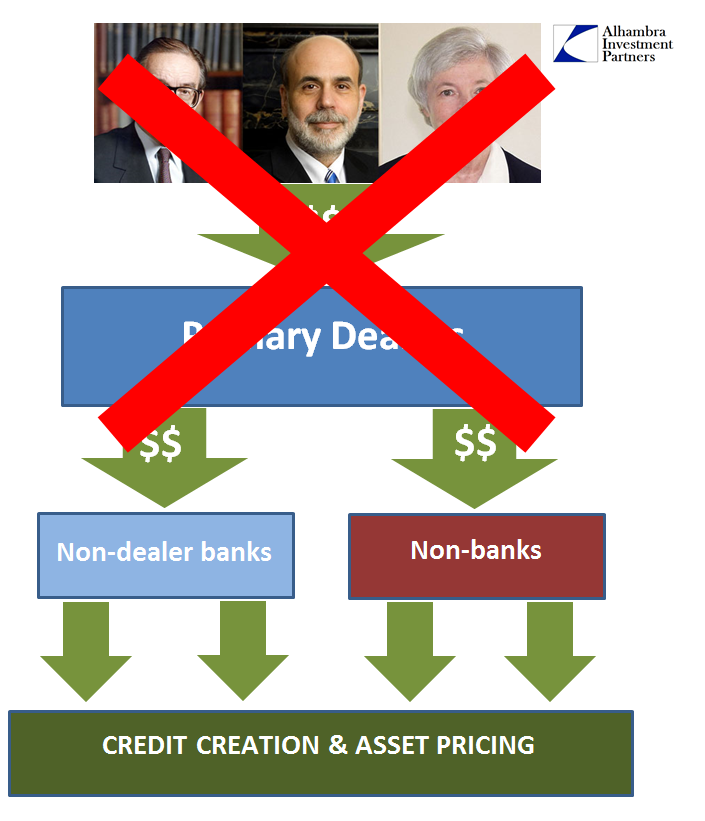

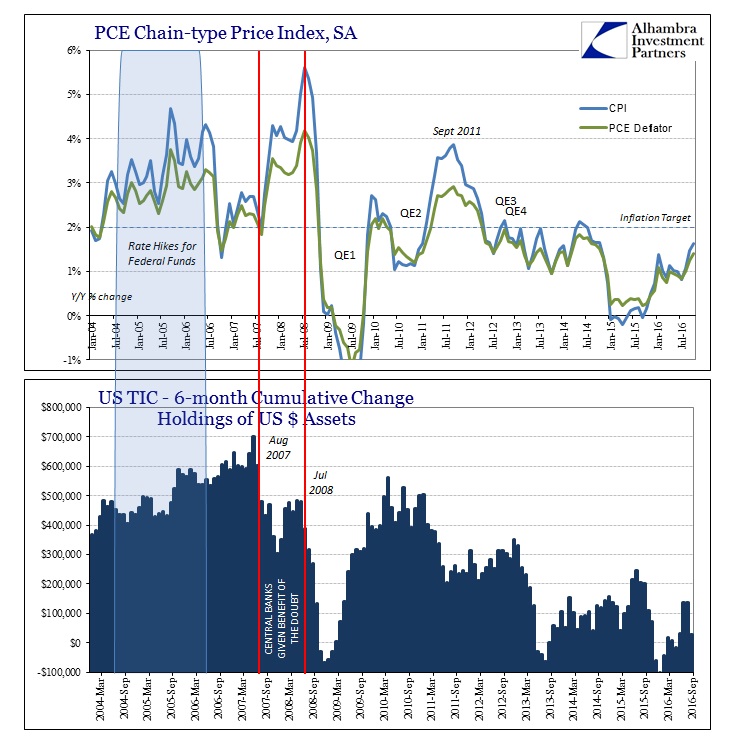

The problem from a monetary policy standpoint that might ever acknowledge this arrangement is that it diminishes greatly the standing of monetary policy and the central bank. To realize that banks are at the center rather than central banks would be for monetary policy to be reduced to one input among many; and, more often than not, especially the past few decades, an unimportant one. We need not search very long for examples of this, as Alan Greenspan’s “tightening” that tightened nothing including calculated inflation in the middle 2000’s is a perfect pre-crisis demonstration of near irrelevance.

On this side of the eurodollar breakdown, the whole affair is and has been, essentially, one of monetary policy impotence; no matter how hard they try, nothing works. The reason is that bank balance sheets are being driven by very different factors, some of them actually related to the failures of QE rather than how they were supposed to have been money printing.

What should be on everyone’s mind now is why it took more than a decade of such direct futility for all this to finally sink in.

The European Central Bank’s money printing scheme is not enough on its own to lift growth because banks in the euro zone are not transmitting cheap credit to the economy due to heightened uncertainty, Governing Council member Ilmars Rimsevics said on Friday.

“It is crucial to understand why commercial banks are not providing sufficient credit to the real economy and why business does not stand in line at banks to borrow money,” said Rimsevics, considered a moderate conservative on the ECB’s rate setting council…

Still, even after 1.5 trillion euros of asset buys, credit growth is lackluster, raising questions about the effectiveness of the scheme, known as quantitative easing.

Leave A Comment