“This reminds me of the late 1960s when we experimented with low rates and fiscal stimulus to keep the economy at full employment and fund the Vietnam War. Today we don’t have a recession, let alone a war. We are setting the stage for accelerating inflation, just as we did in the late ‘60s.”

—Paul Tudor Jones

As soon as the GOP followed its long-promised tax cuts with damn-the-deficit spending increases (who cares about the kids, right?), you knew to be ready for the Lyndon B. Johnson reminders.

And it’s worth remembering that LBJ pushed federal spending higher, pushed his central bank chairman against the wall (figuratively and, by several accounts, also literally) and eventually pushed inflation to post–Korean War highs.

Inflation kept climbing into Richard Nixon’s presidency, pausing for breath only during a brief 1970 recession (although without falling as Keynesian economists predicted) and then again during an attempt at wage and price controls that ended badly. Nixon’s controls disrupted commerce, angered businesses and consumers, and helped clear a path for the spiraling inflation of the mid- and late-1970s.

So naturally, when Donald Trump and the Republicans pulled off the biggest stimulus years into an expansion since LBJ’s guns, butter and batter the Fed chief, it should make us think twice about inflation risks—I’m not saying we shouldn’t do that.

But do the 1960s really tell us much about the inflation outlook today, or should that outlook reflect a different world, different economy and different conclusions?

I would say it’s more the latter, and I’ll give five reasons why.

1—Technology

I’ll make my first reason brief, because the deflationary effects of technology are both transparent and widely discussed, even if model-wielding economists often ignore them. When some of your country’s largest and most impactful companies are set up to help consumers pay lower prices, that should help to, well, contain prices.

2—Globalization

Globalization is another well-worn theme (I can hear the yawns), but it still gets overlooked. In the 1960s, developing countries hadn’t yet found much of a path to US consumers and businesses, such that America’s economy was protected from hundreds of millions of potential dollar-a-day workers. That’s no longer the case, and inflation fundamentals are no longer the same. As long as trade pathways remain open (watch the tariff war), policy makers should find it much harder to cook up inflation than they did fifty years ago.

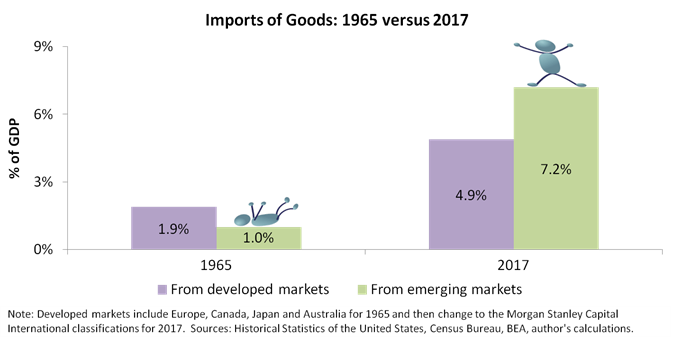

As a measure of globalization, the chart below shows imports of goods separated by whether they come from developed or emerging markets (imports from emerging markets being more likely to dampen inflation) and comparing 1965 to 2017:

Of course, inflation responds not only to specific imports but also to the general threat posed by foreign competition. Nonetheless, the chart confirms the obvious—2018’s economy is less prone to inflation than the insular 1965 economy.

Leave A Comment