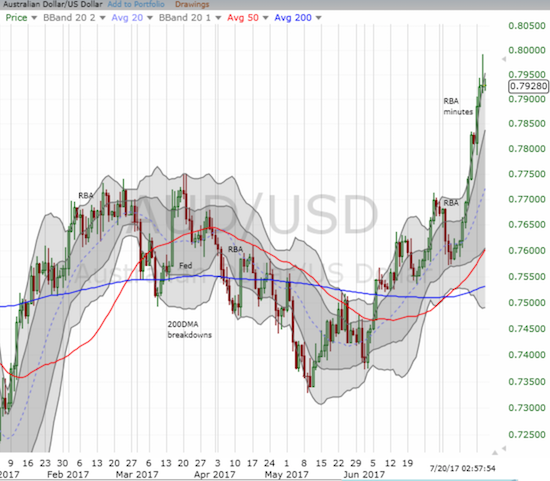

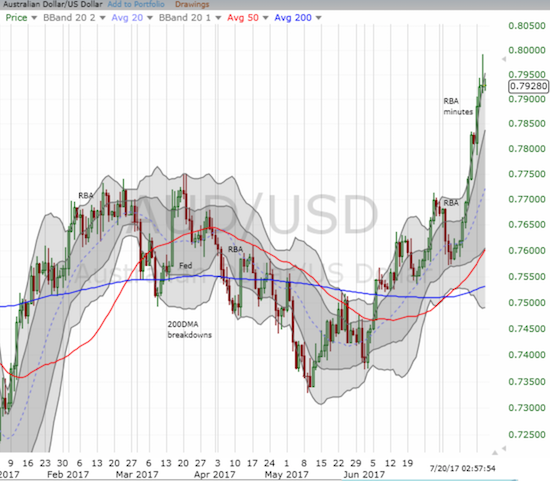

Over two weeks ago I officially ended my bearishness on the Australian dollar (FXA). I made that call just in time.

Against the weakening U.S. dollar, the Australian dollar has gone nearly parabolic. AUD/USD recently touched the 0.80 level, a new 26-month high.

Source: FreeStockCharts.com

The Australian dollar has powered higher against almost all major currencies and now threatens to retard the economy’s on-going adjustment away from mining investment. The Reserve Bank of Australia has consistently noted its reliance on a weaker currency. For example, in the July 4, 2017 statement:

“The depreciation of the exchange rate since 2013 has also assisted the economy in its transition following the mining investment boom. An appreciating exchange rate would complicate this adjustment.”

Ironically, one of the catalysts that helped drive the Australian dollar to its current heights was the RBA itself. In the minutes from the July policy meeting, the RBA decided to discuss explicitly the value of the neutral interest rate – the nirvana rate where monetary policy is neither accommodative nor tight. Certainly even the casual observer of monetary policy already knows that the neutral rates in the countries of all major central banks are much higher than current levels. Moreover, the RBA’s assessment of around 3% is well below the neutral rate before the financial crisis. No matter, currency markets interpreted the very discussion of the neutral rate as an excuse to assume the RBA had abruptly turned hawkish. From the minutes (emphasis mine):

“Members discussed the Bank’s work estimating the neutral real interest rate for Australia. The various estimates suggested that the rate had been broadly stable until around 2007, but had since fallen by around 150 basis points to around 1 per cent. This equated to a neutral nominal cash rate of around 3½ per cent, given that medium-term inflation expectations were well anchored around 2½ per cent, although there is significant uncertainty around this estimate. Members noted that some of this decline could be attributed to lower potential output growth, but the increase in risk aversion around the time of the global financial crisis was likely to have been a more important factor, given that the bulk of the decline in the estimated neutral real interest rate had occurred around that time. Estimates of neutral real interest rates for other economies had shown a similar decline. All estimates of the neutral real interest rate for Australia suggested that monetary policy had been clearly expansionary for the preceding five years or so. It was also noted that a reduction in risk aversion and/or an increase in the potential growth rate could see the neutral real interest rate rise again.”

Leave A Comment