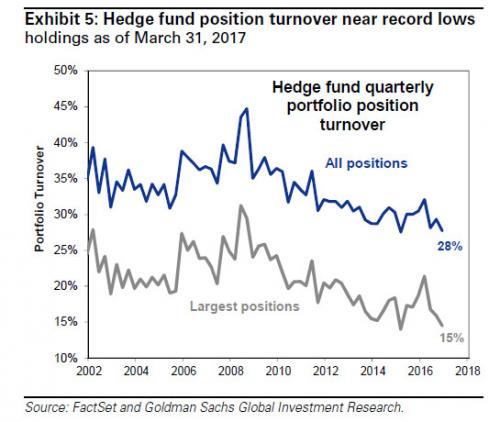

Two weeks ago we asked a question: maybe behind all the rhetoric and constant (ab)use of sophisticated terms like “gamma”, “vega”, CTAs, risk-parity, vol-neutral, central bank vol-suppression, (inverse) VIX ETFs and so forth to explain why despite the surging political uncertainty in recent years, and especially since the US election … global equity volatility, both implied and realized, has tumbled to record lows, sliding below levels not even seen before the 2008 financial crisis, there was a far simpler reason for the plunge in volatility: trading was slowly grinding to a halt.

That’s what we asked a questionwhen looking at 13F filings in Q1, when it emerged that the gross portfolio turnover of hedge funds had retreated to a record low of just 28%. In other words, few if any of the “smart money” was actually trading in size.

Over the weekend, JPM confirmed as much observing that, among other things, it was the retrenchment of active managers, who are being crowded out by central bank QE in the bond space and a shift towards ETFs in the equity space, that acts as long-term depressant of market volatility.

As the bank notes, since the Lehman crisis, the propensity to change positions or trade has declined as active managers have been crowded out by central bank QE, coupled with FX reserve managers’ and commercial banks’ purchases of bonds, all of which are crowding out active bond managers. This crowding out is illustrated in Figure 10 by the ownership of the $54 trillion universe of tradable bonds globally. 50% of this universe is owned by banks, central banks or commercial banks both of which are rather passive owners of bonds.

While the point is critical, what we would like to highlight in the chart below is the staggering amount of debt instruments owned by central banks: as of the latest data, central banks own just over a third of the global tradable bond universe of $54 trillion, or roughly $18 trillion. How this amount of debt on bank balance sheets is ever unwound, i.e. sold – even with central banks’ best intentions – without crashing the bond market, we don’t know.

Leave A Comment