Written by Constantin Gurdgiev, TrueEconomics.Blogspot.in

This week was quite a tumultuous one for banks, and especially Europe’s champion of the ‘best in class’ TBTF institutions, Deutsche Bank. Here’s what happened in a nutshell.

Deutsche’s 6 percent perpetual bonds, CoCos (more on this below), with expected maturity in 2022, used to yield around 7 percent back in January. Having announced massive losses for fiscal year 2015 (first time full year losses were posted by the DB since 2008), Deutsche was under pressure in the equity markets. Rather gradual sell-off of shares in the bank from the start of 2015 was slowly, but noticeably eroding bank’s equity risk cushion. So markets started to get nervous of the second tier of ‘capital’ held by the bank – second in terms of priority of it being bailed in in the case of an adverse shock. This second tier is known as AT1 and it includes those CoCos.

Yields on CoCos rose and their value (price) fell. This further reduced Deutsche’s capital cushion and, more materially, triggered concerns that Deutsche will not be calling in 2022 bonds on time, thus rolling them over into longer maturity. Again, this increased losses on the bonds. These losses were further compounded by the market concerns that due to a host of legal and profit margins problems, Deutsche can suspend payments on CoCos coupons, if not in 2016, then in 2017 (again, more details on this below). Which meant that in markets view, shorter-term 2022 CoCos were at a risk of being converted into a longer-dated and zero coupon instrument. End of the game was: Coco’s prices fell from 93 cents to the Euro at the beginning of January, to 71-72 cents on the Euro on Monday this week.

When prices fall as much as Deutsche’s CoCos, investors panic and run for exit. Alas, dumping CoCos into the markets became a problem, exposing liquidity risks imbedded into CoCos structure. There are two reasons for the liquidity risk here: one is general market aversion to these instruments (a reversal of preferences yield-chasing strategies had for them before); and lack of market makers in CoCos (thin markets) because banks don’t like dealing in distressed assets of other banks. Worse, Asian markets were largely shut this week, limiting potential pool of buyers.

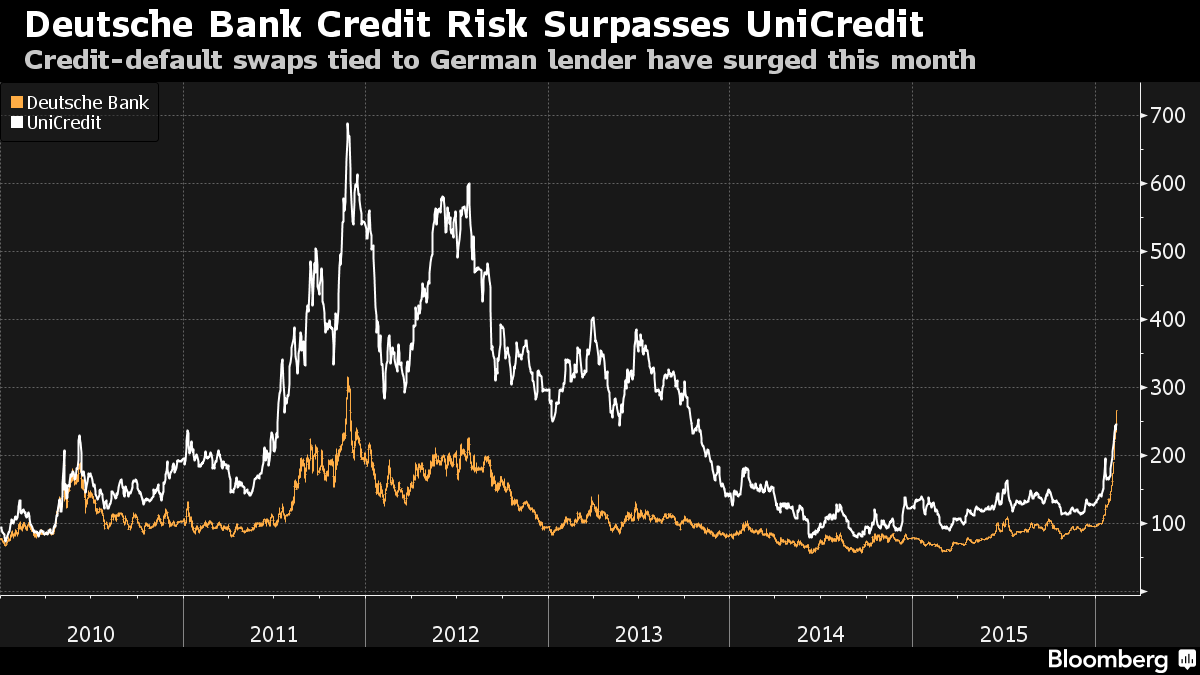

Spooked by shrinking valuations and falling liquidity of the Deutsche’s AT1 instruments, investors rushed into buying insurance against Deutsche’s default on senior bonds – the Credit Default Swaps or CDS. This propelled Deutsche’s CDS to their highest levels since the Global Financial Crisis. Deutsche’s CDS shot straight up and with their prices rising, implied probability of Deutsche’s default went through the roof, compounding markets panic.

Summing Up the Mess: Three Pillars of European Risks

Deutsche Bank AG is a massive, repeat – massive – banking behemoth. And the beast is in trouble.

Let’s do some numbers first. Take a rather technical test of systemic risk exposures by the banks, run by NYU Stern VLab. First number of interest: Systemic Risk calculation – the value of bank equity at risk in a case of systemic crisis (basically – a metric of how much losses a bank can generate to its equity holders under a systemic risk scenario).

Deutsche clocks USD91.623 billion hole relating to estimated capital shortfall after the existent capital cushion is exhausted. A wallop that is the third largest in the world and accounts for 7.23% of the entire global banking system losses in a systemic crisis.

Now, for volatility that Deutsche can transmit to the markets were things to go pear shaped. How much of a daily drop in equity value of the Deutsche will occur if the aggregate market falls more than 2%. The metric for this is called Marginal Expected Shortfall or MES and Deutsche clocks in respectable 4.59, ranking it 8th in the world by impact. In a sense, MSE is a ‘tail event’ beta – stock beta for times of significant markets distress.

How closely does Deutsche move with the market over time, without focusing just on periods of significant markets turmoil? That would be bank’s beta, which is the covariance of its stock returns with the market return divided by variance of the market return. Deutsche’s beta is 1.61, which is high – it is 7th highest in the world and fourth highest amongst larger banks and financial institutions, and it basically means that for 1% move in the market, on average, Deutsche moves 1.6%.

But worse: Deutsche leverage is extreme. Save for Dexia and Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA, the two patently sick entities (one in a shutdown mode another hooked to a respirator), Deutsche is top of charts with leverage of 79.5:1.

Incidentally, this week, Deutsche credit risk surpassed that of another Italian behemoth, UniCredit:

So Deutsche is loaded with the worst form of disease – leverage and it is caused by the worst sort of underlying assets: the impenetrable derivatives (see below on that).

Overall, Deutsche problems can be divided into 3 categories:

These problems plague all European TBTF banks ever since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. The legacy of horrific misspelling of products, mis-pricing of risks and markets distortions by which European banks stand is contrasted by the rhetoric emanating from European regulators about ‘reforms’, ‘repairs’ and ‘renewed regulatory vigilance’ in the sector. In truth, as Deutsche’s saga shows, capital buffers fixes, applied by European regulators, have yielded nothing more than an attempt to powder over the miasma of complex, derivatives-laden asset books and equally complex, risk-obscuring structure of new capital buffers. It also highlights just how big of a legal mess European banks are, courtesy of decades of their maltreatment of their clients and markets participants.

Leave A Comment