Today’s release of U.S. data on wages growth for October should give the Federal Reserve members some pause for concern when they meet in December. In nominal (current dollars) terms, wages have moved up a modest 2.4 % over the past 12 months. Economists prefer to measure wage performance in real terms— discounted for the effects of inflation. Here the wage data is a real cause for concern. Real wages increased over the same time period, although at a much more reduced rate of 0.4%. Since August, however, the real average hourly earnings have actually fallen slightly from $10.78 in September to $10.76 in October. The decrease in real average earnings stems from a combination of 0.1 % increase in the CPI and no change in the average workweek. (Figure 1).

This decline in real wages took place during a relatively good GDP performance. If real economic growth is accelerating, as many believe, then workers are clearly not reaping the benefits. They are getting neither more pay per hour nor more overtime. Wages are clearly not a source of inflationary pressures. And, one could argue that the wage stagnation has much to do with deflationary pressures, especially as profit growth has been relatively robust.

Figure 1 U.S. Wage Growth

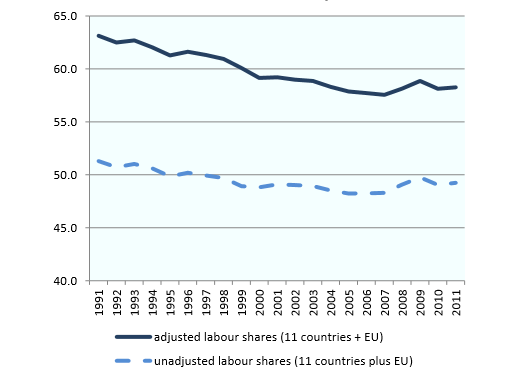

National income is split between wages and profits. For more than two decades, labor’s share of the national income pie has been on a steady decline. Today’s wage data just continues this unmistakable pattern of declining labor income share (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Labour Share of National Income, OECD Countries

Such trends in labor shares have a negative impact on macroeconomic components such as personal consumption, private sector investment, and government revenues. Furthermore, this decline in labor’s share contributes much to the disruptive political developments present in developed countries.

Leave A Comment