In February of 2018 the financial dam welling up all asset prices sprang a leak, demonstrating to newer investors that markets can actually go down – a lot, and fast. However, the Fed’s derivative finger was quickly applied to plug up the hole, and financial waters again started to rise toward their previous level. With a current change in Federal Reserve’s leadership and direction, we are likely to experience increased market volatility with attendant significant and frequent fluctuations in asset values.

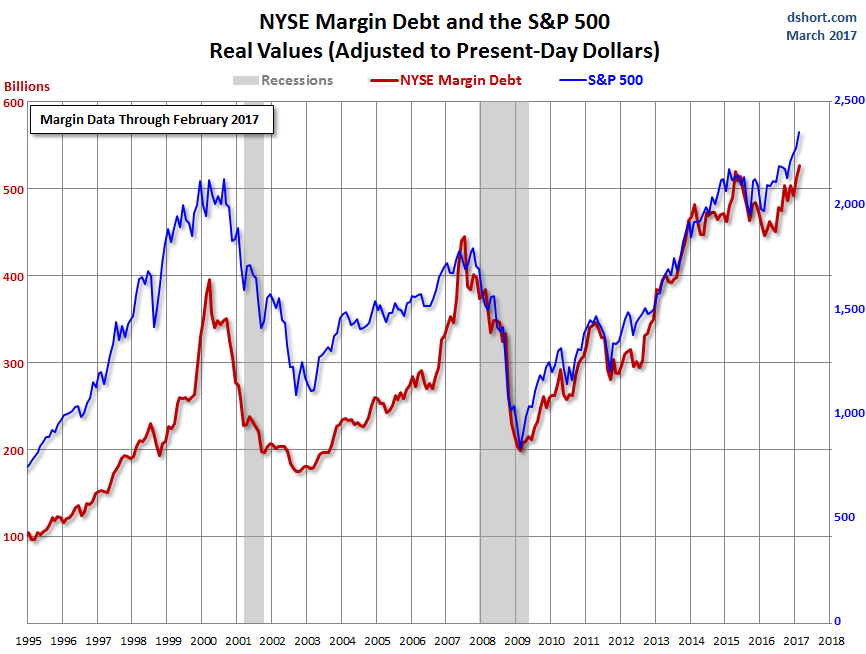

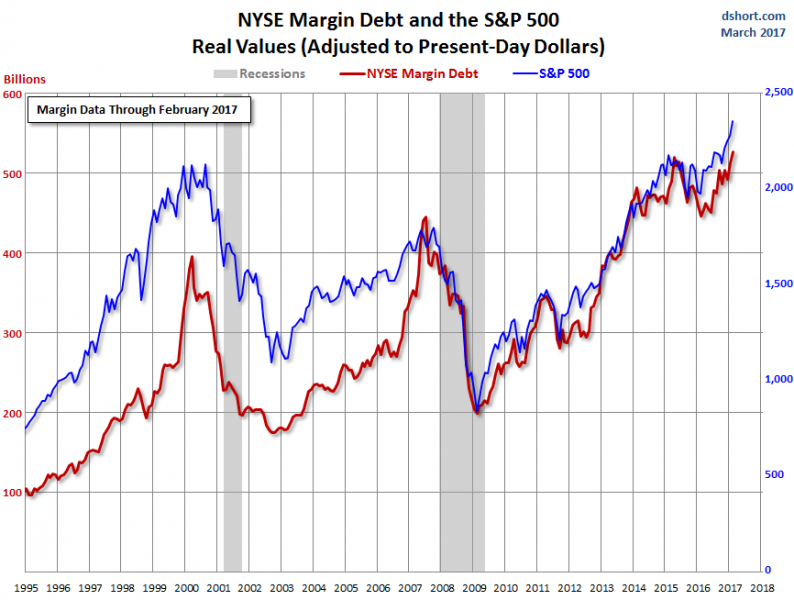

The partial recent recovery in financial markets likely provides comfort to those who in February experienced record declines in their investment portfolios. However, no such comfort should be taken. The high level of confidence among professional money managers previously relying on loose monetary policy by the Fed-levitating our equity and fixed income markets had caused a high percentage of money relative to total portfolio assets to be already invested, which leaves little cash reserves to further stimulate or maintain present market prices. And record high margin of debt among individual investors as well as hedge funds provides little room for additional borrowed money to add new investment into these markets. Rising interest rates or a modest market correction could easily start a more serious market decline, driven by margin calls and liquidation of assets.

Note in the preceding chart that at both market peaks in 2000 and 2007, margin debt had concomitantly risen to record heights. But more important is the rise in margin debt to even higher levels since the last market peak. Note also, that if one purchased stock in 2000 it took another eight years to break even; if one purchased stock in 2007, it took about seven years to break even. Our current markets index suggests that it may take an equal or longer time to break even after the current peak.

Similarities to the Great Depression

Our financial markets appear to be in a situation not dissimilar to that of the Great Depression of the late 1920’s, where stock market margin debt was record high, and interest rates were being raised by the Fed to reduce speculation. Over the last ten years, investors have been gaming the Fed by participating in markets as long as there is excessive money printing, euphemistically called quantitative easing.

At the time of the Great Depression, our government called for tariffs on foreign goods which accelerated economic decline and extended the depression. Recently president Trump has called for tariffs on steel and aluminum, which could be the single rolling stone that starts the global tit for tat avalanche of trade-restrictive policies. Protective tariffs can be vital to protecting and maintaining production capacity in strategically vital industries, and therefore are important for national security considerations. However, tariffs on trade did not help the global economy of the 1930’s; and this time such a gambit could be far more dangerous because of our large national debt held by foreign sovereign countries – for a trade war could escalate to the point where foreign U.S. Treasury security holders sell such securities into the open market either because of budgetary need or retaliation, starting a rout of our own bond and currency market.

Globalism and free markets

Over previous decades, the United States has been the primary leader in promoting globalism and free trade. As the country which was omnipotent after WWII, the emerging dollar as a globally preferred currency was a boon to America. Increasing trade based on America’s then great manufacturing infrastructure and the destruction of competing manufacturers due to devastating war bombing promoted increased economic and financial global dominance by the U.S. So arguing for “free trade”, which required other countries to reduce their tariffs, was an advantage to America.

At that time increasing the amount of currency by the Fed also worked incredibly well, because it allowed America’s elite to purchase war-torn foreign manufacturing operations at pennies on the dollar, or provide foreign investment dollars which translated into large equity ownership shares of strategic foreign businesses, or lend money on foreign government-backed surefire country projects at very attractive rates as those countries clamored to get more dollars for post-war rebuilding. Even after the closing of America’s gold window in 1971, demand for the dollar continued, as the ingenious idea of oil being purchased globally with only the use of dollars was sold to Saudi Arabia. Monetary growth facilitated veiled financial warfare which was then presented as generous country-saving or developing infrastructure loans. It took decades of actual borrowing experience before debtor countries collectively understood that the IMF and the World Bank were also America’s post-war financial warriors and conquerors.

Leave A Comment