“In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, a weighing machine.” -Ben Graham, Warren Buffett’s teacher at Columbia and the founder of modern value investing

All our lives we make quick decisions. Do we watch CSI or Masterpiece Theater? Buy an Edsel or a Mustang, Tide or Cheer, Crest or Colgate? Vote for Sally Hairdo Von Airbrain or Sue Rocket Scientist, Bill Babbler Booby or Joe Genius? Over time, we learn that to act in haste leads to bad decisions—we repent at leisure. As we age, we weigh options more carefully before we decide.

So too with the stock market.

The stock market is an auction market. Through humans and computers, the stock exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq manage buying and selling. They maintain order books, which used to be actual paper, pencil and pen, but today are constantly changing electronic lists of offers sent by brokerage houses to buy or sell shares of stock in a company. The “bid” is the highest price a buyer will pay at the moment and the “ask” is the lowest at which a seller will sell. When prices match, a trade occurs.

Supply and demand rule the market. More buyers? Prices rise until the supply of sellers increases to match buyer demand. When there are more sellers, the price falls until the supply of buyers matches seller demand.

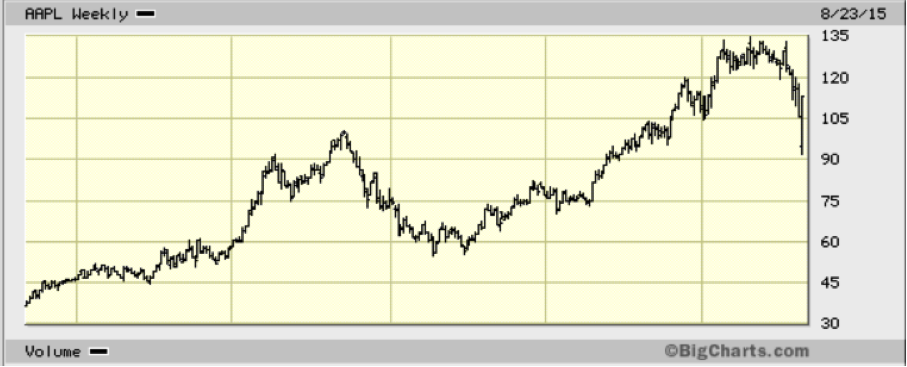

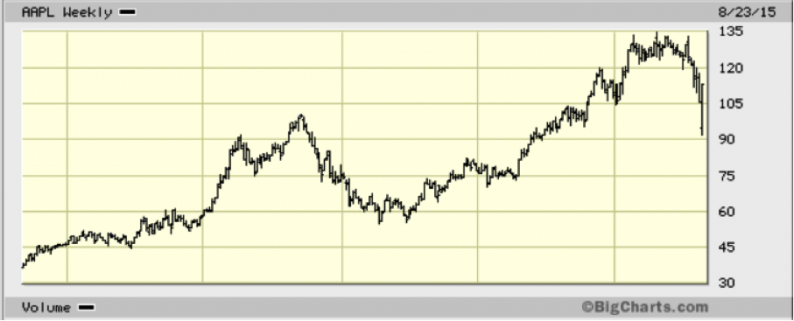

The shorter the time period, the more stocks rise and fall as buyers and sellers act—vote—based on popularity and emotion. In the longer run, buyers and sellers weigh the value of this business or that to make considered decisions. You can see this at work in any stock’s price history. Here is the 5-year price chart for Apple, the largest company by market cap in the world:

Even though Apple’s five-year direction has been up, there have been significant drops. Spread this out side to side and more drops appear dramatic in shorter periods. This works for stocks that slump over time, too. Their prices show short periods in which they jump.

Leave A Comment