The payroll reports are most often assigned a level of credibility that strains credibility. As if written in stone delivered from the infallible, they are the economic stats that most people pay attention to and from where they derive most of their views on the economy. This isn’t without some good reason, as in prior economic periods there was a very good correlation between the various payroll reports and all the rest of the economic data. If the unemployment rate was low, it wasn’t at all surprising to find almost all other estimates corroborating that view. In other words, the BLS data had become shorthand for everything else.

In reality, the payroll reports are statistical monstrosities, a Frankenstein’s monster of so many different regressions, normalizations (trend-cycle), and benchmarking. The benchmarking process is supposed to create more robust data, and that can be the case, but it can also make a further mess of things. When I write that I believe (still) that the BLS overstated the employment figures especially in 2014, it is often met with disbelief (especially from the media) as if that were ever possible. The payroll report for January 2017 was an almost perfect storm exemplifying all these weaknesses hidden in plain sight.

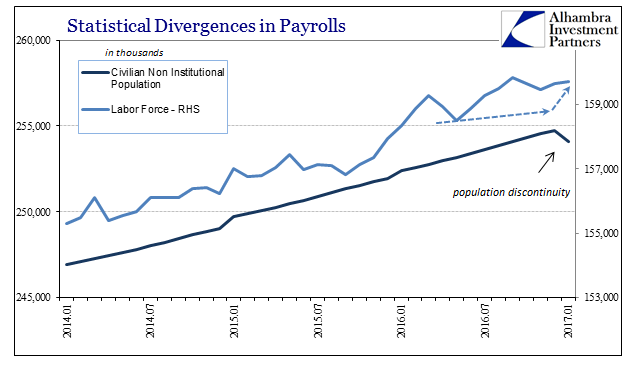

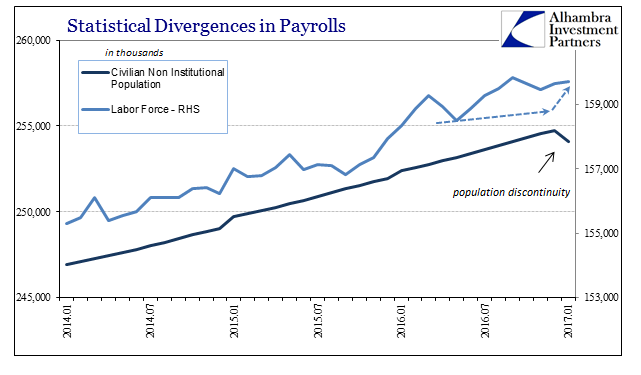

To start with, 660,000 potential workers disappeared last month. The BLS draws upon Census Bureau population statistics which are, outside the decennial Census, like everything else statistical models of survey results, and therefore require periodic adjustments to correct “errors” (which are themselves statistical models). For January 2017, the BLS reports that a large population adjustment was made indicating that the Census Bureau overestimated the Civilian Non-Institutional Population during 2016. We don’t know by how much or in what particular months, all we know is that in keeping with standard policy the BLS created a discontinuity in the population data that filters into all the Household Series.

The data series for the official Labor Force, for example, shows a net change of just 76k in January, another seemingly paltry advance belying the mainstream idea of a “strong” labor market. The new population figures, however, lead the BLS models to suggest that the gain in January was instead 584k, and that their estimates for 2016 were in some way cumulatively about 500k lower.

Leave A Comment