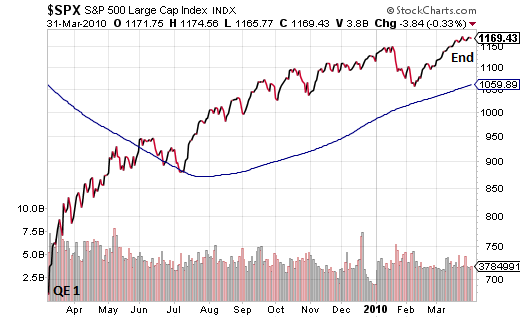

Since the Great Recession’s inception, whenever the stock market dropped like a steel anvil or the U.S. economy showed signs of weakness, the Federal Reserve acted to inspire investor confidence. For example, in November of 2008, when the Fed announced its first quantitative easing (QE1) program to buy mortgage-backed securities (MBS), stocks rocketed 10% in two weeks. The enthusiasm wore off quickly. In March of 2009, the central bank of the United States “doubled down” on the MBS dollar amount and simultaneously expanded its reach with a decision to acquire $300 billion of longer-term Treasury bonds. The 1-year program correlated with stock market gains of 70%.

Could the Fed have stopped there? At the end of the first quarter in 2010? The Fed could have. However, when the S&P 500 lost 16% over the next few months, committee members began hinting at a second tidal wave of bond buying (QE2). From summertime rumor through QE2 completion in the second quarter of 2011, the S&P 500 pole vaulted approximately 29%.

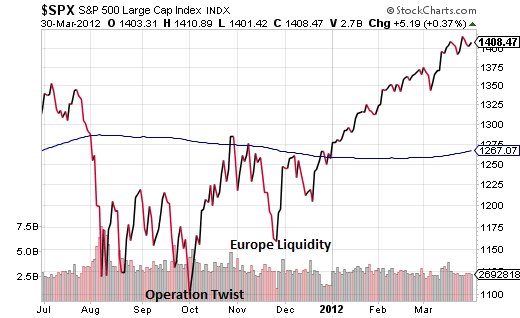

Might the monetary policy authorities have decided, at that juncture, to let financial markets operate without additional interference? At the conclusion of the second quarter of 2011? They might have. Perhaps unfortunately, the S&P 500 responded unfavorably to the end of another Federal Reserve program and the absence of a European bank bailout. A 19% price collapse over a brief span of time compelled the Fed to invoke “Operation Twist” – a program to push borrowing costs even lower through using the proceeds of short-dated Treasury bond maturities to acquire intermediate- and long-dated maturities. The Federal Reserve also orchestrated dollar liquidity swap arrangements that aided European financial institutions with raising capital. Not surprisingly, the Fed-inspired activities helped push U.S. stocks 27% off of the 2011 bottom.

“Operation Twist” was scheduled to end in the second quarter of 2012. What could possibly go wrong? This time, investors did not even wait for another Fed program to end, sending stocks down nearly 10% over 8 weeks in April-May. The Fed did not wait either. They extended “Operation Twist” through year-end 2012. And there was more. In an effort to break the cycle of start-stop stimulus dates, and to stimulate a U.S. economy that showed definitive signs of deceleration, the Fed served up hints of its largest quantitative easing experiment yet. The third round of asset purchases (QE3) was not only larger than its predecessors at $85 billion per month, it was open-ended in nature; that is, it came without a formal termination date. Over the next three years, the S&P 500 catapulted roughly 57% with little resistance.

Leave A Comment