Forecast

Analysis

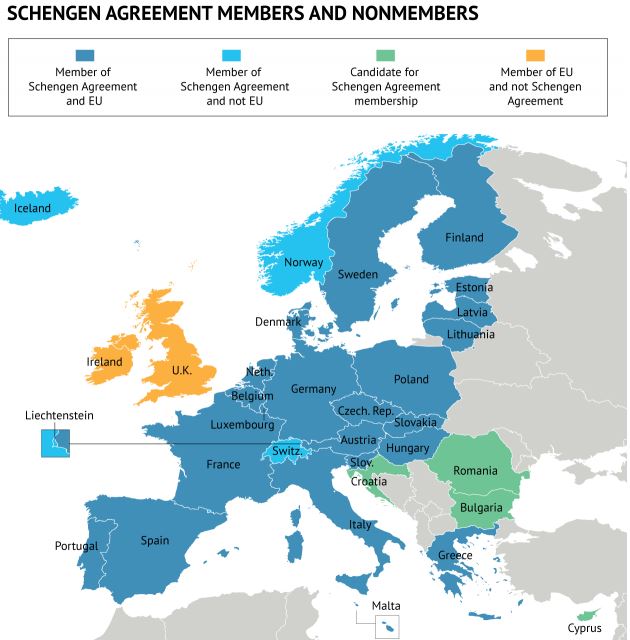

When France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg signed the Schengen Agreement in 1985, they envisioned a system in which people and goods could move from one country to another without barriers. This vision was largely realized: Since its implementation in 1995, the Schengen Agreement eliminated border controls between its signatories and created a common visa policy for 26 countries.

The treaty was a key step in the creation of a federal Europe. By eliminating border controls, member states gave up a basic element of national sovereignty. The agreement also required a significant degree of trust among its signatories, because it put the responsibility for checking foreigners’ identities and baggage on the country of first entry into the Schengen area. Once people have entered a Schengen country, they can move freely across most of Europe without facing any additional controls.

The Schengen Agreement was implemented in the 1990s, when the end of the Cold War and the prospect of permanent economic prosperity led EU members to give up national sovereignty in many sensitive areas. The creation of the eurozone is probably the most representative agreement of the period. But several things have changed in Europe since then, and member states are beginning to question many of the decisions that were made during the preceding years of optimism.

The most important change of the past six years is probably Europe’s economic crisis and its byproduct, the rise of nationalist political parties. Not far behind, though, is the substantial increase in the number of asylum seekers in Europe, which is putting countries on the European Union’s external borders (such as Greece and Italy) and countries in the Continent’s economic core (such as France and Germany) under significant stress. This is not the first time the Schengen Agreement has been questioned, but the combination of a rising number of asylum seekers, stronger nationalist parties and fragile economic recovery are leading governments and political groups across Europe to request the redesign, and in some cases the abolishment, of the Schengen Agreement.

On the one hand, countries in northern Europe criticize countries on the Mediterranean for their lack of effective border controls and for their failure to fingerprint many of the asylum seekers that reach EU shores. This means that the migrants can move elsewhere in the Continent to apply for asylum. In recent months, French and Austrian authorities accused Rome of allowing (and even encouraging) asylum seekers to leave Italy and threatened to close their borders with Italy; indeed, France followed through with its threat and briefly closed its border in late June.

Leave A Comment