In recent decades the global economy has been transformed by the rise of the emerging market economies. Their growth lifted millions out of poverty and gave their governments the right to call for a larger voice in discussions of international economic governance. Therefore it is of no small importance to understand whether recent declines in the growth rates of these countries is a cyclical phenomenon or a longer-lasting transition to a new, slower state. That such a slowdown has wide ramifications became clear when Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen cited concerns about growth in emerging markets for the delay in raising the Fed’s interest rate target in September.

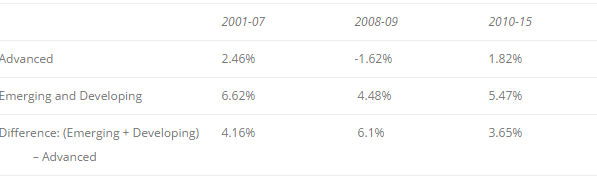

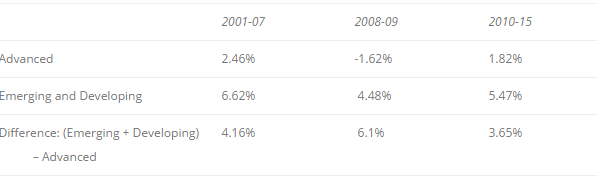

The data show the gap between the record of the advanced economies and that of the emerging markets. I used the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database to calculate averages of annual growth rates of constant GDP for the two groups.

The difference in the average growth rates was notable before the global financial crisis, and rose during the crisis. Since then their growth rates have fallen a bit but continue to exceed those of the sclerotic advanced economies. Since the IMF pools emerging market economies with developing economies, the differences would be higher if we looked only at the record of emerging markets such as China, India and Indonesia.

And yet: behind the averages are disquieting declines in growth rates, if not actual contractions, for some members of the BRICS as well as other emerging markets. The IMF forecasts a fall in economic activity for Brazil of -3.03% for 2015 and for Russia of -3.83%, which makes South Africa ’s projected rise of 1.4% look vigorous. Even China’s anticipated 6.81% rise is lower than its extraordinary growth rates of previous years, and exceeded by India’s projected growth of 7.26%. The IMF sees economic growth for the current year for the emerging markets and developing economies of 4% , a decline from last year’s 4.6%.

Leave A Comment