Until the 1970s, all recorded history showed that bond yields were tied to the general price level, not the rate of price inflation as commonly believed. However, since then, the statistics say this is no longer the case, and bond yields are increasingly influenced by the rate of price inflation. This article explains why this has happened, and why it is important today.

This paper is a follow-up on my white paper of October 2015.[i] In that paper, I explained why, based on over two-hundred years of statistics, long-term interest rates correlated with the general price level, and not with the rate of inflation. I now take the analysis further, explaining why the paradox appears to no longer apply.

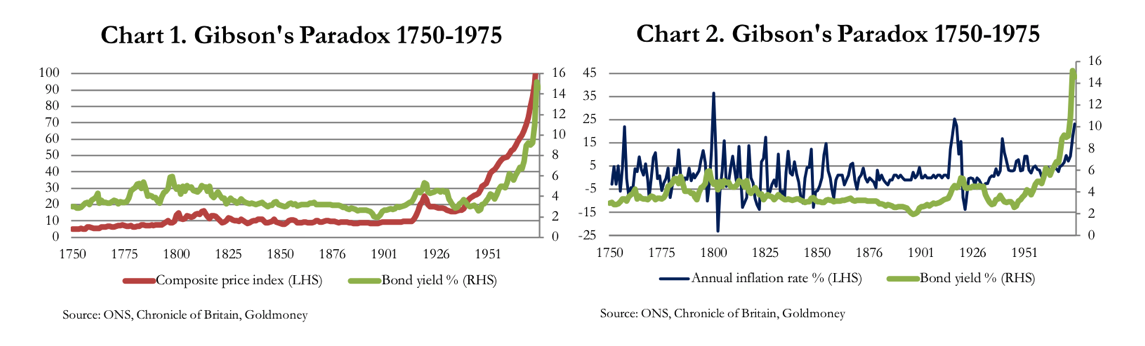

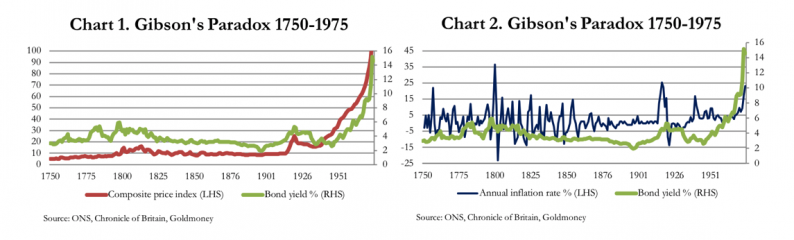

The two charts which illustrate the pre-seventies position are Chart 1 and Chart 2 reproduced below.

The charts take the yield on the UK Government’s undated Consolidated Loan Stock (Consols) as proxy for the long-term interest rate, and the price index and its rate of change (the rate of price inflation) as recorded in the UK. The reasons for using UK statistics are that Consols and the loan stocks that were originally consolidated into it are the longest running price series on any form of term debt, and during these years Britain emerged to be the world’s leading commercial nation. Furthermore, for the bulk of the period covered by Gibson’s paradox, London was the world’s financial centre, and sterling the reserve basis for the majority of non-independent foreign currencies.

The evidence from the charts is clear. Gibson’s paradox showed that the general price level correlated with long-term interest rates, which equate to the borrowing costs faced by entrepreneurial businessmen. It did not correlate with the rate of change in the general price level, otherwise known today as the rate of price inflation. It contradicts the monetary theories prevalent over the period from David Ricardo onwards. In other words, there is no empirical evidence that using interest rates as the means of regulating demand for debt, and therefore economic activity actually works. And that should worry us.

The paradox was first identified by Thomas Tooke in 1844 but named by Keynes after Alfred Gibson, who wrote an article about it for Banker’s Magazine in 1923. Keynes called it a paradox because he could find no explanation for it, and besides a number of futile attempts over the years to explain it, it remained a paradox until I was able to solve the riddle in 2015.

The solution was disarmingly simple. A businessman planning to manufacture a product would have to work out his production costs on known factors. His assessment of the product’s future market value was always based on known prices for similar goods. He was then in a position to calculate what interest rate he was prepared to pay over the time taken to deliver his output to the market if he needed to borrow to manufacture the product. It was through this calculation process that the cost of borrowing was tied to wholesale values reflected by a price index.

The widespread assumption in economic textbooks has always been that savers alone set the interest rate when allocating spending between current and deferred consumption. I found only one exception to the view that savers set the rate, and that was almost an aside in Ludwig von Mises’s Theory of Money and Credit. He stated that the demand for capital takes the form of a demand for money.[ii]

So, money is demanded by the manufacturer. Mises’s view of the setting of interest rates, which Keynes in his General Theory professed to not understand[iii], overturns longstanding religious and socialist prejudices about the role of the saver. According to von Mises, the saver provides a service to businessmen by making capital available for production, for which the businessman readily pays. Going back a page in von Mises’s Theory of Money and Credit, we find that he also held that:

Capital goods or production goods derive their value from the value of their prospective products, but as a rule remain somewhat below it. The margin by which the value of capital goods falls short of that of their expected products constitutes interest; its origin lies in the natural difference between present goods and future goods.[iv]

This being the case, clearly, the rate of interest is set by what the borrower will pay to secure profitable production of future goods, not what a usurious rentier, as Keynes and others had it, will demand. The businessman sets the price of borrowing by having the option not to borrow, or to change his plans. In his calculations, he will attempt to quantify his fixed and marginal costs of production, and the added production additional capital will provide. He must estimate the wholesale value of his extra production, to assess his profits, gross of interest. He must allow for the time taken from gathering together the elements of monetary and non-monetary capital to the product being sold, by assessing the time-preference involved. He is then able to judge what interest he is prepared to pay to secure the capital required for a viable proposition.

But there is a further wrinkle on this, which secures the solution to Gibson’s paradox. If interest rates are too high for a particular production plan, the businessman might modify his plans to accommodate them, because higher borrowing costs are broadly matched by a generally higher level of prices. The higher level of prices is the consequence of an increased level of consumption relative to savings, and a lower rate of saving will tend to raise the interest cost of business funding. Therefore, changes in the general price level must correlate with the cost of business funding. The relationship between time preference (represented by interest rates) and how production adapts is the background to Hayek’s triangle.[v]

Clearly, the businessman sets interest rates by bidding them up to the point where savings match his plan, so long as borrowing to fund his production promises to yield an acceptable profit. This tells us something we should have known all along: consumers would rather spend than save and, all else being equal, have to be tempted to save. This is the central truth, which all those who tried to explain Gibson’s perplexing paradox, including Tooke, Arthur Gibson, Irving Fisher, Knut Wicksell, and JM Keynes himself, failed to grasp. Larry Summers even put his name to a paper on the subject which was equally unsatisfactory.[vi]

One must add that this still held true if consumers increased their propensity to save, thereby driving the level of interest rates lower, and by switching from current to deferred consumption, driving the general price level lower as well. As Hayek showed, lower prices and lower interest rates made it profitable for businesses to invest in more roundabout means of production to match the lower prices that result from a change in the balance between current and deferred consumption.[vii] But businesses were still price-makers in the context of lower rates.

The reason the great and the good got it so wrong must be in their psyche. It is fundamental to Christianity, and the other monotheistic religions as well, to regard interest as usury. A usurious person is traditionally seen to be an evil idler, a Shylock, someone who extracts money from others simply because they have money to lend, while the hard-working producer does all the work. A saver being paid interest is cast as a leech on society. This prejudice is certainly visible in Keynes’s writings. He called savers rentiers, a term with a slight pungency to it, which conjures up an image of a collector of rents on behalf of the landowner. He even called for the saver’s euthanasia in his General Theory.

No wonder the economic establishment missed the point, that the producer wants the saver’s money, which the average saver is generally reluctant to provide.

Much follows from this insight. The whole Christian-socialist ethos depends on Keynes’s rentier being morally inferior to the borrower. There is a statist preference for the plight of the debtor over the rights of the creditor, not just because the state is a debtor itself. If, as we can conclude from explaining Gibson’s paradox, the debtor is not an innocent party legged-over by greedy rentiers and therefore not entitled to claim a moral high-ground, we must fundamentally change our views on interest.

Economists in the Austrian tradition understand differently from this mainstream view. Admittedly, they rarely addressed which party is the price-maker in this matter. Furthermore, Murray Rothbard’s unfinished history of economics is one of only a small number of important works on the subject that have the philosophical and religious antipathy towards interest as a central theme.[viii] Indeed, an understanding, free from moralizing, of the relationship between producers and consumers is a sine qua non for all economic analysis. But what should worry us all is that the basis of central bank interest rate policy is aligned with the moralists in defiance of the empirical evidence in Gibson’s paradox.

Leave A Comment