You find lots of tortured arguments about the state of the economy, largely because the premise starts with the boom and then seeks to find it. If it isn’t currently visible in the data, there is unusual and unearned confidence that the data will have to change in the near future (rather than the past three times we’ve been through this where the narrative is what ends up differently).

It’s a curious development, though understood plainly for the reasons I detailed earlier. The economy in narrative is booming now, so the economy in data, which isn’t, will be booming later.

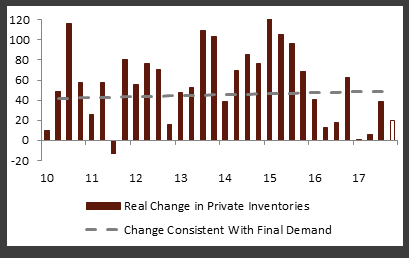

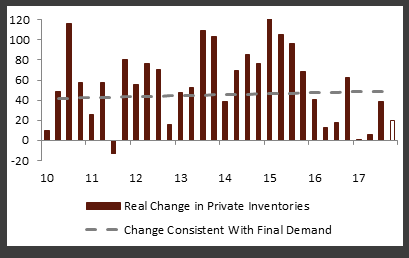

One data-based measure of this discrepancy is inventory, a subject we’ve covered before. Inventory accumulation in 2017 was low. Compared to 2014, it was practically nil. Some take that to mean inventory will lead US expansion in 2018 to great things.

From Bloomberg last month:

First, U.S. inventory investment is simply too low. Although the contribution of inventories to growth can be volatile from quarter to quarter, inventories tend to grow in line with final sales over longer periods of time. Today, that simply is not happening; inventories have been trailing the growth in domestic demand. If the economy expands at 2.2 percent, the rough trend since the end of the recession, inventories would need to grow by about $50 billion per year to keep pace with demand. Inventories ran below that level in 2017. That means factories are likely to go into overdrive to boost inventories in coming quarters.

The chart accompanying the article is reproduced above. The author completely ignores everything before, about how inventory rose so far above the rate consistent with final sales particularly 2014-15. The reason for lower inventory growth in 2016-17 is therefore obvious. Unless sales pick up substantially above the moribund 2% pace, there is no reason for businesses to order up the anticipated “factory overdrive.” They did that four years ago to negative effect.

Leave A Comment