Image Source: Pexels

Image Source: Pexels

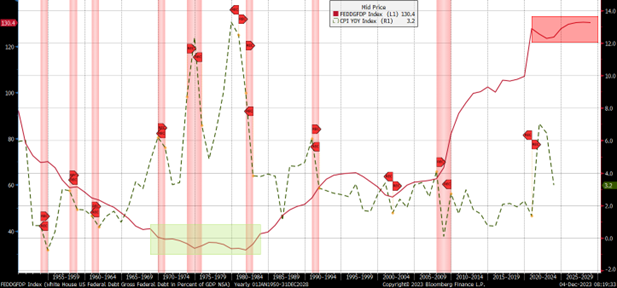

The year 2008 and the subsequent Global Financial Crisis (GFC) stand as a watershed moment in the annals of our capitalist society. It was a bailout prompted by poor capital allocation, deficient risk management, and unchecked greed. More significantly, it marked a seismic shift, both financially and psychologically. Financially, it represented a substantial transfer of debt from corporate and private balance sheets to the balance sheet of the US Government. Psychologically, it sent a clear message to investors: if you are deemed systemically important, the degree of risk mitigation employed matters little in terms of being held accountable.Fast forward to the present day. We’ve experienced over 13 years of artificially low or negative real interest rates, several rounds of quantitative easing (QE), and Operation Twist (essentially QE by another name). This all culminated in helicopter money to address the COVID pandemic, regional bank liquidity injections, and the ironically named Inflation Reduction Act. It’s hardly surprising, except perhaps to the academics at the Fed, that we are witnessing an uptick in inflation.So the question is, have we seen peak inflation and has the Fed found the magic formula to stem spending while not significantly impacting employment? If so, the Magnificent 7 can continue their linear assent ad infimum as artificial intelligence (AI) becomes the next future generational revenue driver for the bulls to chase. However, if the past is any indication, the answer is no. We have mentioned before that this macro environment is very similar to the previous inflationary period of the 1970s, which had three peaks before being tempered. Instead of baby boomers with Johnson administration guns and butter, we have millennials, ESG, and a pandemic. As the chart below shows, it’s not unheard of for inflation to come in waves.U.S. Inflationary Periods 1910, 1939, 1972, 2021 Source: BloombergThere are, however, notable differences that distinguish the 1970’s environment from today, and they fundamentally limit the Fed’s options. The primary distinction becomes apparent when examining the chart below. When Volcker came into the picture in 1979, he had to raise rates to a peak of 20% in 1981 to curb inflation effectively. Aside from his political autonomy and fortitude to follow through, one contributing factor to the success of this strategy was the comparatively modest Federal budget deficit, amounting to a mere 40% of gross domestic product (GDP). In stark contrast, the present budget deficit has surged to ~130% of GDP.Green line – CPI YOY , Red line – US Federal Debt to GDP

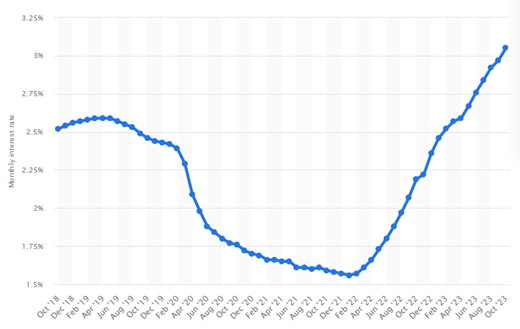

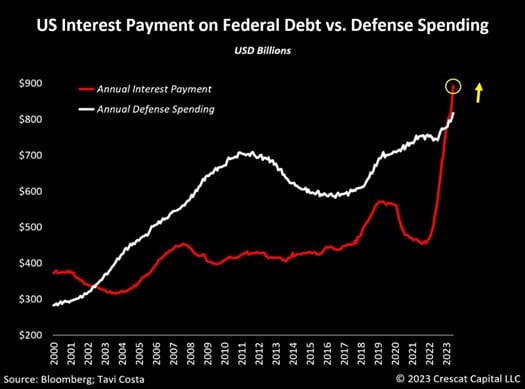

Source: BloombergThere are, however, notable differences that distinguish the 1970’s environment from today, and they fundamentally limit the Fed’s options. The primary distinction becomes apparent when examining the chart below. When Volcker came into the picture in 1979, he had to raise rates to a peak of 20% in 1981 to curb inflation effectively. Aside from his political autonomy and fortitude to follow through, one contributing factor to the success of this strategy was the comparatively modest Federal budget deficit, amounting to a mere 40% of gross domestic product (GDP). In stark contrast, the present budget deficit has surged to ~130% of GDP.Green line – CPI YOY , Red line – US Federal Debt to GDP Source: BloombergThe government’s cost to combat inflation has undergone a significant shift. For instance, the duration of outstanding public debt is comparatively shorter with approximately 50% set to mature in the next two years. This correlates to a quick uptick in interest costs, which we are now seeing. At the start of 2023, the average interest rate on the roughly $31 trillion of federal debt was around 2.7%, up from about 2% a year earlier. The Federal government is currently paying at 3.05%. As a result, the United States’ interest payment costs now exceed our annual defense spending (we are only a little over a year into tightening). We will leave it up to the reader’s imagination as to what programs our politicians have the political will to trim, even outside of an election year (our guess is zero).

Source: BloombergThe government’s cost to combat inflation has undergone a significant shift. For instance, the duration of outstanding public debt is comparatively shorter with approximately 50% set to mature in the next two years. This correlates to a quick uptick in interest costs, which we are now seeing. At the start of 2023, the average interest rate on the roughly $31 trillion of federal debt was around 2.7%, up from about 2% a year earlier. The Federal government is currently paying at 3.05%. As a result, the United States’ interest payment costs now exceed our annual defense spending (we are only a little over a year into tightening). We will leave it up to the reader’s imagination as to what programs our politicians have the political will to trim, even outside of an election year (our guess is zero). Source: Statista

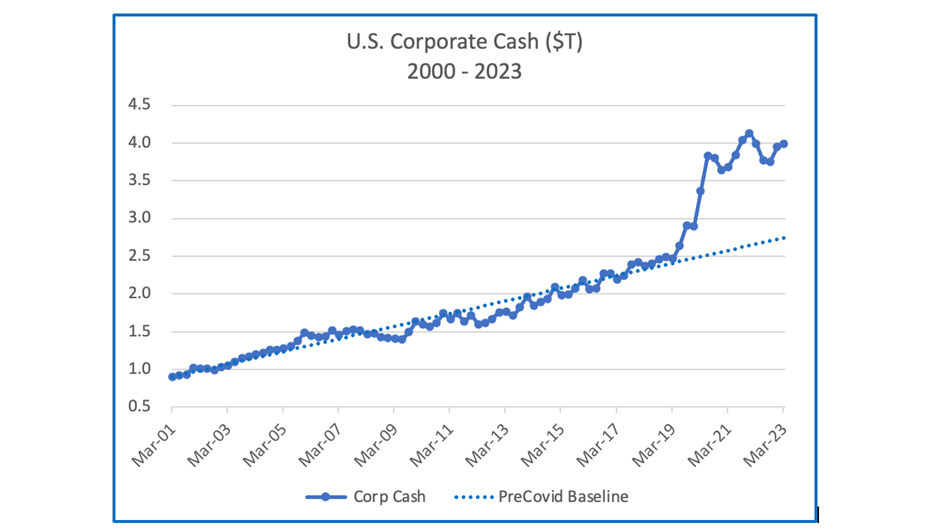

Source: Statista Compare the Government debt schedule to that of companies. Only ~15% of corporate debt is maturing within two years.

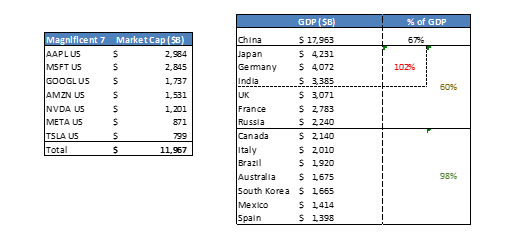

Compare the Government debt schedule to that of companies. Only ~15% of corporate debt is maturing within two years. The Fiscal and Monetary theory of today is in stark contrast to the pre-1970s era. When things were challenging back then, the government typically maintained a balanced budget and allowed poorly allocated business investments to liquidate. Today, companies and consumers have ample cash reserves. The Magnificent 7 have near monopolies on their respective markets; combined they make up 30%1 of the S&P 500 and their combined market caps are greater than the GDP of Japan, Germany, and India combined.2

The Fiscal and Monetary theory of today is in stark contrast to the pre-1970s era. When things were challenging back then, the government typically maintained a balanced budget and allowed poorly allocated business investments to liquidate. Today, companies and consumers have ample cash reserves. The Magnificent 7 have near monopolies on their respective markets; combined they make up 30%1 of the S&P 500 and their combined market caps are greater than the GDP of Japan, Germany, and India combined.2 Source: BloombergWhat would be the Fed’s strategy in the event we have additional waves of inflation? It appears that the options involve either letting inflation run well above the two percent target in an attempt to reduce interest payments via the devaluation of the dollar and/or come down hard on the economy. The former seems politically more feasible, but only time will tell.We think this quote from Jeffrey Gundlach at Grant’s 40th Anniversary: “Rates Can Never Rise” sums up the position the Fed has put itself in. “Jay Powell kind of stepped in it when he decided he was going to use Supercore inflation, so PCE core less shelter, I mean you’re down to what, boxes of pencils? What are we measuring here? I mean there’s no food, there’s no energy, there’s no shelter. I mean what it is? FanDuel spending?”3People often sacrifice resilience for stability or some other more immediately recognizable system property. They want things to happen in their normal life cycle, but these cycles take decades, and when they break, they hit you in the face like stepping on a rake.More By This Author:Stock Market Psychology

Source: BloombergWhat would be the Fed’s strategy in the event we have additional waves of inflation? It appears that the options involve either letting inflation run well above the two percent target in an attempt to reduce interest payments via the devaluation of the dollar and/or come down hard on the economy. The former seems politically more feasible, but only time will tell.We think this quote from Jeffrey Gundlach at Grant’s 40th Anniversary: “Rates Can Never Rise” sums up the position the Fed has put itself in. “Jay Powell kind of stepped in it when he decided he was going to use Supercore inflation, so PCE core less shelter, I mean you’re down to what, boxes of pencils? What are we measuring here? I mean there’s no food, there’s no energy, there’s no shelter. I mean what it is? FanDuel spending?”3People often sacrifice resilience for stability or some other more immediately recognizable system property. They want things to happen in their normal life cycle, but these cycles take decades, and when they break, they hit you in the face like stepping on a rake.More By This Author:Stock Market Psychology

Artificial (Stock Market) Life Support

Energy Magicians

Leave A Comment