<< Read More: Part I – “Buy & Hold” Can Be Hazardous To Your Wealth

<< Read More: Part II – Why Crashes Matter & The Saving Problem

<< Read More: Part III – Valuations & Forward Returns

<< Read More: Part IV – The Math Of Loss

<< Read More: Part V – Choosing The Right Portfolio Benchmark

<< Read More: Part VI – Should You Invest Like Warren Buffett?

<< Read More: Part VII – The Myths Of Stocks For The Long Run

<< Read More: Part VIII – The Myths Of Stocks For The Long Run

<< Read More: The Myths Of Stocks For The Long Run – Part IX

CHAPTER 10 – Risk Knows No Age

“If you are a young investor, you need to take on as much risk as possible. The more risk you take, the greater the reward.”

This is actually a false statement.

Let’s start with the definition of “risk” according to Merriam-Webster:

1: possibility of loss or injury : peril

2: someone or something that creates or suggests a hazard

3a : the chance of loss or the perils to the subject matter of an insurance contract; also : the degree of probability of such loss

3b : a person or thing that is a specified hazard to an insurer

3c : an insurance hazard from a specified cause or source

4: the chance that an investment (such as a stock or commodity) will lose value

Nowhere in that definition does it suggest a positive outcome for taking on “risk.”

In fact, the more “risk” assumed by an individual the greater the probability of a negative outcome. We can use a mathematical example of “Russian Roulette” to prove the point.

The number of bullets, the prize for “surviving,” and the odds of “survival” are shown:

While there are certainly those that would “eat a bullet” for their family, the point is simply while “more risk” equates to more reward, the consequences of a negative result increases markedly.

The same is true in investing.

At the peak of bull market cycles, there is a pervasive, cancerous dogma communicated by Wall Street and the media which suggests that in the long run, stocks are a “safe bet,” and risk is somehow mitigated over time.

This is simply not true.

Blaise Pascal, a brilliant 17th-century mathematician, famously argued that if God exists, belief would lead to infinite joy in heaven, while disbelief would lead to infinite damnation in hell. But, if God doesn’t exist, belief would have a finite cost, and disbelief would only have at best a finite benefit.

Pascal concluded, given that we can never prove whether or not God exists, it’s probably wiser to assume he exists because infinite damnation is much worse than a finite cost.

A recent comment from a reader further confirms what many investors to believe about risk and time.

“The risk of buying and holding an index is only in the short-term. The longer you hold an index the less risky it becomes.”

So according to our reader, the “risk” of losing capital diminishes as time progresses.

First, risk does not equal reward. “Risk” is a function of how much money you will lose when things don’t go as planned. The problem with being wrong, and facing the wrath of risk, is the loss of capital creates a negative effect to compounding that can never be recovered.

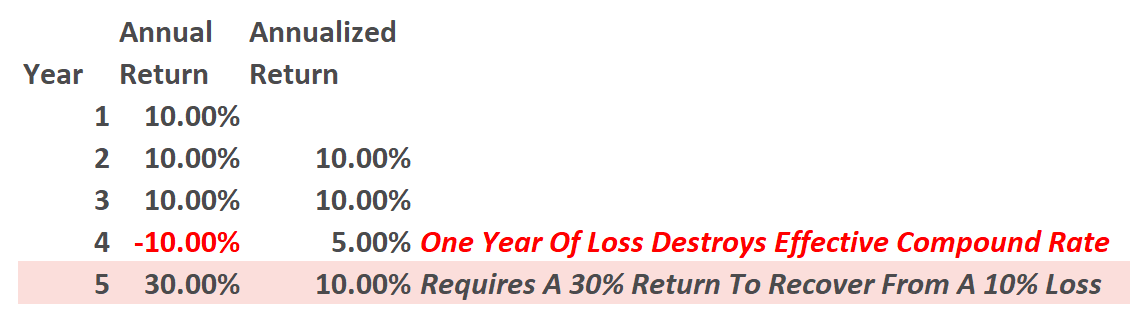

As we showed previously, let’s assume an investor wants to compound investments by 10% a year over a 5-year period. The table below shows what happens to the “average annualized rate of return” when a loss is experienced.

The “power of compounding” ONLY WORKS when you do not lose money. As shown, after three straight years of 10% returns, a drawdown of just 10% cuts the average annual compound growth rate by 50%. Furthermore, it then requires a 30% return to regain the average rate of return required. In reality, chasing returns is much less important to your long-term investment success than most believe.

Leave A Comment