Effective June 10, 2014, the European Central Bank cut the interest rate it paid on its deposit account to less than zero. That instrument in forming the floor for what is a money market corridor in European policy, it was the world’s first major NIRP experiment. Europe’s economy had by GDP been growing again for three straight quarters by then after a re-recession in 2012 extending into the first quarter of 2013 completely upset the delicate post-2008 recovery balance.

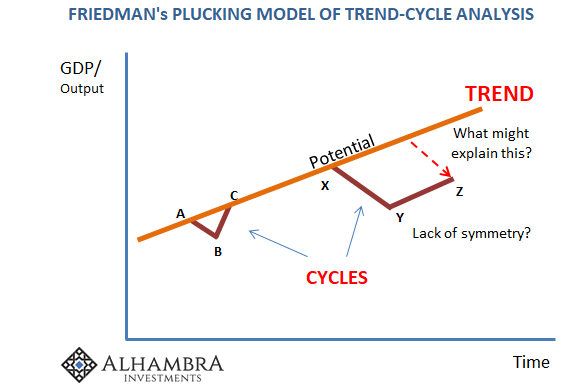

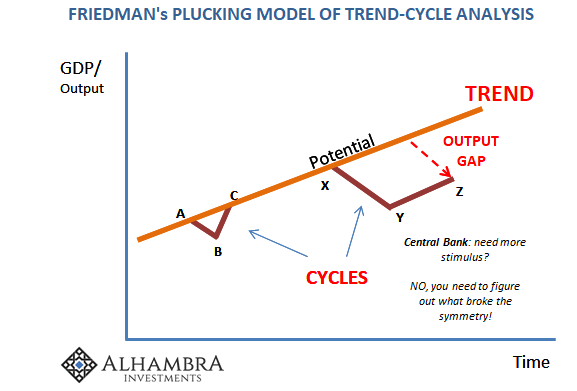

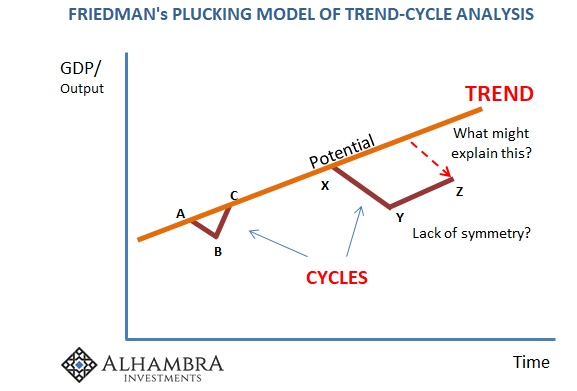

The purpose of NIRP was to ensure this re-recovery would remain on track. Already there was a problem just in that reasoning. After nearly a year of recovery, “re” or not, there really shouldn’t be much involvement of policy or any kind of “stimulus.” Symmetry rules of any business cycle dictate that once an economy starts back upward, it goes upward without assistance.

In fact, that had been the defining mandate for monetary policy throughout the previous few years. Its intended role was to get the economy to switch signs, to end the negatives so that the economy would naturally progress as it always had in business cycles where positives would on their own proliferate.

Even the ECB in 2014 knew that low level positives after both the massive Great “Recession” and then this 2012 re-recession weren’t right. Europe’s economy was growing, but it wasn’t growth; symmetry was conspicuously absent. Thus, what policymakers attempted in 2014 was to create it by experiment.

It has been a universal, worldly problem not limited by any means to that particular geography or its idiosyncratic imbalances (of which are substantial). Ten years later, the entire globe is still talking about “stimulus” for lack of symmetry.

The switch to NIRP was by no means the only emphasis. Just three months after setting the deposit account at -10bps, the ECB in September 2014 reset it to -20bps.

Outside the money market floor, the central bank began buying up all manner of financial assets. On October 2014, they initiated their third round of covered bond purchases (a security somewhat unique to European banking). A month later, it was ABS. By March 2015, it was the big one everyone had been waiting for – the Public Sector Purchase Program, or PSPP, which is commonly known as QE. That was eventually expanded and then by the middle of 2016 they were buying corporate bonds, too. The deposit account had by then been set at -40bps.

Leave A Comment