Last week, when looking back at consensus economist forecasts for Japanese growth as of 1995, we compared what the pundits thought would happen, and what actually did happen: the result was what may have been the worst forecast of all time, leading to a 25% error rate in just five years later. It also unleashed the start of Japan’s three lost decades.

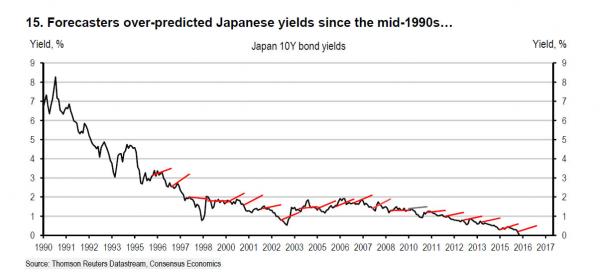

But while laughably wrong economist forecasts are nothing new, a more troubling observation emerges when comparing the evolution of Japan’s 10Y yields start in the 1990s…

…with those in the rest of the western world, which are slowly converging with Japan and the Y-axis.

Looking at Japan’s miserable fate ever since the bursting of the 1980 asset bubble, HSBC’s Stephen Major recently said that “finding an explanation for Japan’s ongoing economic weakness is a bit of a ‘chicken and egg’ problem. Was the high level of debt associated with the bubble the key constraint on subsequent economic expansion? Or was the unexpectedly-weak economic expansion a key reason why debt was so indigestible? In truth, the causality ran in both directions, suggesting that Japan – at least in nominal terms – found itself caught in a ‘doom loop’, a world in which policy stimulus did little to help Japan return to the dynamism seen in earlier decades.”

King then extrapolates the case study of Japan’s “deflationary stagnation” to the “slow puncture” he observes in the rest of the developed world, and provides several ways of previewing of what may lie in store for the world if using Japan as the canary in the coalmine.

As he says, the world economy’s slow puncture reflects five factors:

In Japan’s case, escape from stagnation has proved difficult. Admittedly, the Japanese authorities were slow to recognise the nature of the problem in the early-1990s, cutting interest rates only slowly, offering little in the way of fiscal stimulus and dragging their feet on bank restructuring.

In the late-1990s, however, the Japanese banking system was restructured, removing some of its initial ‘doom loop’ problems. Two decades later, the Bank of Japan, under Haruhiko Kuroda, has done exactly what many thought would eventually deliver results: massive balance sheet expansion, a clearly-articulated ambition to raise the inflation rate and a substantial currency devaluation. Yet, despite all this, the path for nominal GDP has barely changed. Perhaps those policies would have worked in a world where Japan was the only country facing deflationary stagnation. As deflationary stagnation has spread, however, the efficacy of these policies appears to have declined.

This leads us to King’s rhetorical question du jout: “Given this disappointment, what options are available for the rest of the industrialised world?”

This is his extended answer:

Ultimately, policy has to deal with one of two variables. Either debt has to come down or income has to rise. Otherwise deleveraging is likely to persist and the air will continue to escape from the global economy. Low interest rates should, in theory, help on both counts. By reducing debt service costs, they should make it easier to reduce the outstanding stock of debt and, by making saving less attractive, they should encourage people to spend more. Yet if nominal economic activity still remains weak at the zero rate bound – as, indeed, ithas in recent years – other options may need to be pursued.

Both quantitative easing and negative nominal interest rates can provide more support. Both, however, have their limitations.

Quantitative easing may have lifted asset prices and stopped a 1930s-style meltdown but households and companies have mostly been unwilling to spend freely. Meanwhile, the main beneficiaries financially are those already asset rich who, typically, have a low marginal propensity to consume.

If, for political, social and reputational reasons, banks find it difficult to impose negative interest rates on their depositors, negative interest rates in effect become a tax on banks.

As a result, the banks’ willingness to take on more deposits will be lowered, limiting their role as financial intermediaries. Other things equal, if banks turn depositors away, the money will end up under the mattress (in which case, the velocity of circulation of money will decline, limiting the impact of negative rates on nominal GDP)

So what else can be done?

The fiscal option

Central to Larry Summers’ argument in favour of ‘secular stagnation’ is the idea that weak demand will, in time, damage supply potential. It’s an old argument, based on the idea that under-utilised resources eventually decay thanks to ‘hysteresis’. Far better, therefore, todeliver a boost to demand that will prevent resources from standing idly by. Higher demand will prevent supply from atrophying. Put simply, demand safeguards its own supply.

Leave A Comment