Both technological developments and international trade can disrupt an economy, and in somewhat similar ways, but many people have very different reactions to these forces. To illustrate the point, I sometimes pose this question:

There’s a US company which has developed a new technology that allows them to make a certain product more cheaply. This company hires some additional workers, but the other firms trying to make that same product don’t have the technology, so they lay off workers or even go bankrupt. Should step be taken to ban or limit the use of this new technology?

Pause for thought. The usual reaction that emerges from the discussion is that we can’t hope to freeze technology in place. Ultimately, we don’t want to be a society with lots of workers who light gas streetlamps, or who operate telegraphs or who plow fields with oxen. Sure, it’s important to have social policies to cushion the transition to new industries, but overall, we need to be facilitating new technology rather than blocking it.

All of which is fair enough, but here’s the kicker. Now you discover that the “new technology” from the US firm is that it is importing more cheaply from a foreign provider. The same disruption of the US labor force is occurring but as a result of an expansion of international trade rather than as a result of technology. Personally, my response to the economic disruption of trade is essentially same as my response to the economic disruption of technology: that is, I believe in assisting the transition for dislocated workers no matter the reason behind the dislocation. But for many people, their reaction to economic disruption is different depending on whether the underlying cause is technology or trade.

Their arguments are renewed and refreshed in a couple of recent publications. J. Bradford DeLong has written “When Globalization Is Public Enemy Number One” in the most recent issue of the Milken Institute Review (Fourth Quarter 2017, 19:4, pp. 22-31). Also, the

World Trade Report 2017 from the World Trade Organization is centered on the theme, “Trade, Technology, and Jobs.”

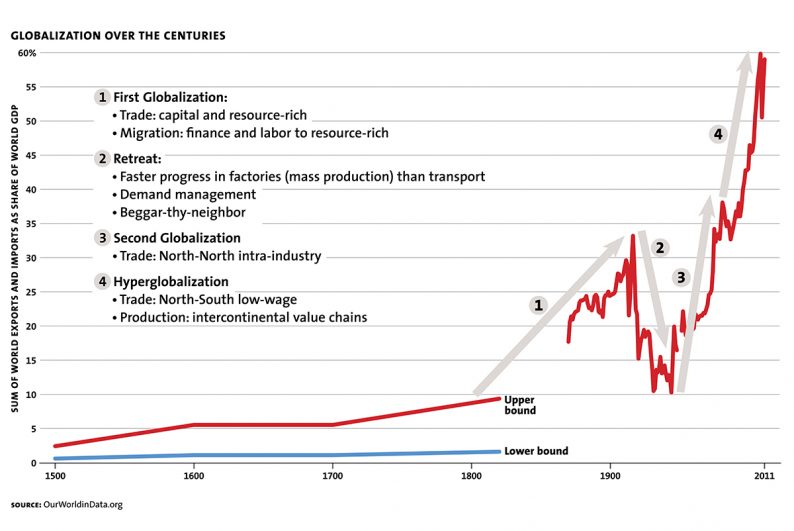

As a starting point, here’s a figure from DeLong’s paper about the rise of globalization. The red line shows the sum of exports and imports compared to world GDP. The first explosion of globalization starting in the 19th century, and the more recent rise of globalization, are both readily apparent.

But of course, a rise in trade isn’t the only economic change taking place. Brad points out that the fall in blue-collar and manufacturing jobs was well underway back in the 1950s and 1960s, well before globalization had restarted in force–because of changes in technology Indeed, I’ve written before about “Automation and Job Loss: The Fears of 1964” (December 1, 2014). Brad readily admits that the shock of increased trade with China starting around 2001 was an important event, and of course, the Great Recession had a powerful effect on jobs too. But overall, he writes:

By his calculations, only a very minor part of the decline in blue-collar jobs since 1948 is about international trade: it’s mostly about technological change, and to some extent about the rising strength of economies in other parts of the world and misjudgments of macroeconomic policy by the US government.

Leave A Comment