If I had to pick one event that led to the housing bubble and subsequent financial crisis, it wouldn’t be difficult…

The answer is easily the erosion of the Glass-Steagall Act — also known as the U.S. Banking Act of 1933.

In the purest spirit of the legislation, Glass-Steagall was intended to keep commercial banking and investing banking separate.

It worked quite well for the first 30 years.

But greed would ultimately triumph over prudence.

Banks began figuring out that Glass-Steagall was a hindrance to growth in the early 1960s.

By 1962, under lobbying pressure, bank regulators began interpreting Glass-Steagall differently.

So the thin red line between commercial banking and investment banking was already blurring — that is, before Bill Clinton fired the kill-shot in 1999 officially repealing Glass-Steagall.

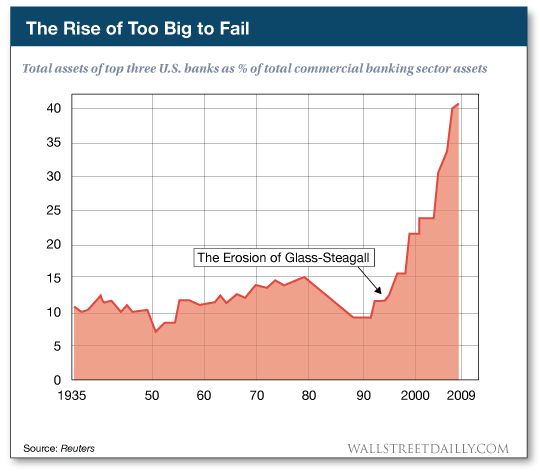

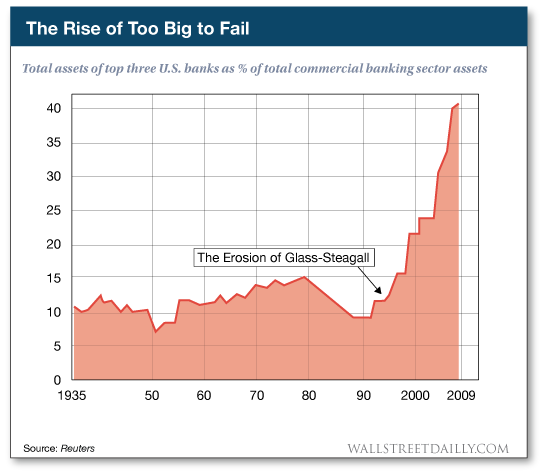

The chart below shows how the demise of Glass-Steagall gave rise to the term “too big to fail.”

But now there’s a movement within the Trump administration — driven by top economic aide Gary Cohn — to put Glass-Steagall back on the books.

Such a move would send profound aftershocks across the financial system.

So I asked my senior analyst, Martin Hutchinson, to get the scoop.

Is this more empty rhetoric from Republicans… or should we be preparing our portfolios?

Hutch’s full analysis is below.

Ahead of the tape,

Louis Basenese

Chief Investment Strategist

Question: Martin, Gary Cohn says he wants to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act, which was repealed in 1999. What’s that all about?

Martin Hutchinson: Cohn is the director of the Council of Economic Advisers in President Trump’s Cabinet. So when he says something like that, particularly since he’s ex-Goldman Sachs, one pays attention. It’s something that could happen.

Glass-Steagall in the 1930s split commercial and investment banks. Then the 1999 legislation allowed them to re-merge again.

Leave A Comment