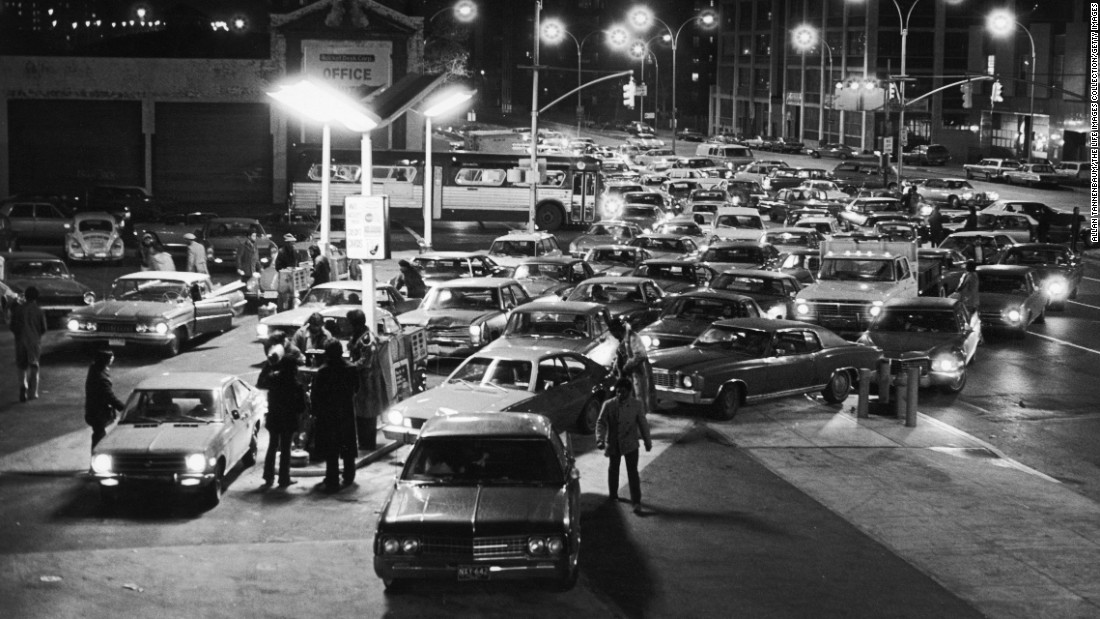

When we look back at the period known as the Great Inflation there is a tendency, I believe, to truncate the episode only to the most well-known parts. What many people remember are things like gas lines, where oil problems and embargoes left Americans at several points in the seventies too often stuck for trying to fill up their autos (or just the household lawn mower).

It’s very easy, then, to fall into the assumption that the Great Inflation was mostly petro issues concentrated in the 1970’s. Those were, in fact, symptoms of a greater problem that began actually in the mid-1960’s.

For the first part of that earlier decade, consumer prices remained low and stable. Around 1965, however, they jumped in a sustained fashion. The reasons for the Great Inflation are several, including the growing acceptance of the exploitable Phillips Curve offered by economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow. The idea was that the government might trade off inflation for employment, tolerating more of the former to “buy” less unemployment.

Alan Meltzer’s fabulous history of the Federal Reserve identifies the central bank’s legacy “even keel” policy as one of the proximate causes, too. Owing to lingering commitments from when the Fed was obliged to place a ceiling on UST rates, after 1951 it no longer entered the government bond market for that reason but it still increased the level of reserves ahead of each treasury auction so as to guarantee smooth function. At some sufficient period afterward, the Fed would then drain reserves to balance out.

In 1965, the Johnson Administration decided in part due to Samuelson and Solow to pursue both the Great Society as well as communists in Vietnam. The exploding budget deficits spooked markets (the remnants of Bretton Woods) while also forcing the Fed into constant reserve liquidity; treasury auctions became so frequent and large that there was simply no time to remove so much “accommodation.” It simply built up until it was far too late.

Leave A Comment