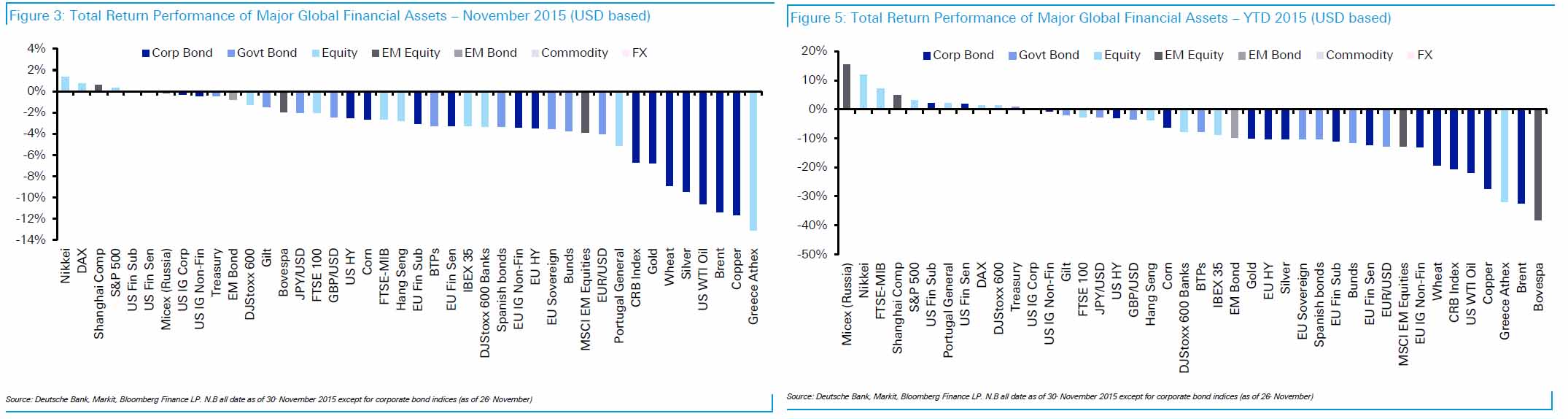

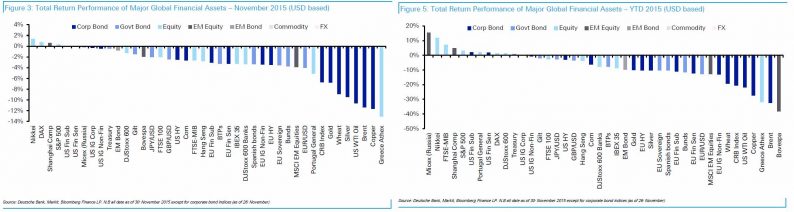

As we noted earlier when looking at the best performing assets of 2015, a curious picture has emerged: denominated in local currencies, there are quite a few assets that have generated substantial returns as the year draws to a close. However, in USD terms the picture is starkly different with the vast majority of USD-redenominated assets generating negative returns.

As DB’s Jim Reid summarized, “very few global asset classes have gone up in Dollar terms this year. Russian equities (+15.6%) and the Nikkei (+11.8%) have been the notable outperformers while European credit is in double digit negative returns which is the case also for European sovereign bond markets. So in a world of a stronger dollar it’s been very difficult to generate positive dollar returns in 2016. With so many dollar investors at a global level this surely has to have had a big impact on the mood of 2015 and confidence.“

It is not just risk assets, of course: as we first profiled back in February, the entire global economy,when denominated in dollars, will see a dramatic GDP contraction of over $2 trillion as a result of the strengthening dollar.

This is a theme that SocGen’s Andrew Lapthorne has been covering extensively over the past several months, as covered most recently in “What Will Happen To Corporate Profits If The Fed Hikes In December.”

He continues today, picking up on the theme of divergence in USD vs non-USD returns, saying that “the translation effect of the US dollar is having a big impact on overall performance. Quoted in almost any other currency 2015 looks fairly healthy, but this performance disappears when it is translated into US dollars. Eurozone investors may appear better off, given double-digit returns on many of the headline eurozone indices this year, but in reality this is largely down to the debasement of the currency, and after big US dollar gains in November, more than 4%, the euro is now down almost 13% YTD, and in US dollars eurozone equities are negative this year.“

This is why, as the SocGen note is titled, it is “all about the US dollar” according to Lapthorne.

He then says that in a world in which local-currency denominated asset growth is almost entirely driven by currency devaluation, “what matters next is whether these competitive devaluations can lead to volume growth and market share gains.”

His answer is that so far, having moved first, “it is only Japan that has seen a meaningful boost to profits beyond simple translation effects. No doubt helping to explain the strong Nikkei performance this year, even in US dollars, and despite Japan falling back into recession. The Japanese have learned their lesson from the rapid yen appreciation in the 1990’s, but as we mentioned in a Quant Quickie a couple of weeks ago, the US is at risk of suffering the same fate.” That note can be found here.

Lapthorne then notes the strange divergence which we pointed out earlier today when remarking on the drubbing in global commodities:

Whilst most global sectors fell last month, the brunt of the selling was seen in the Oil E&P Industrials Metals and Mining sectors, driven lower by continuing disappointing data out of China and once again collapsing commodity prices. Oil, copper, iron ore and silver, to name just a few, were all down by 9% or more during November.

However, one market emerged largely unscathed in November: “The exception to this global picture is in the US, where sector performance was a Pavlovian response to the much expected upcoming US rate rises (Utilities down and Basic Materials up). Global investors may be cyclically bearish, but US investors appear distracted by the historically cyclically positive message US rate rises might imply. We think this may prove a mistake.”

Which is logical: after years of rewarding stocks for a weaker dollar, over the past year we have seen the market flip as the correlation has inverted and stocks rise with the dollar. Which is great if the Fed is right and the dollar is up for the right reasons, but is a huge gamble if the strong dollar merely reflects the unprecedented easing by all the other central banks, whose sole intention is so boost their own exports, corporate profitability and share of global trade in a zero sum space.

Which is also the basis for Lapthorne’s warning: for now the market is hypnotized by the Fed’s inexplicable eagerness to hike rates even as the Manufacturing ISM tumbles below 50 and with Q4 GDP now projected to drop to just 1.4% annualized, and is convinced there is something “just around the corner” that is not obvious to market participants, but the Fed is aware of.

Alas, that is almost certainly not the case, especially considering the Fed’s track record of “seeing behind corners” or even “contained” things in plain sight.

And while we agree that US investors are largely oblivious to what everyone else is seeing, the question remains: what is the catalyst that will make them see. Perhaps the reality of Q4 earnings which will be a disaster should the dollar continue its rise, will finally reprice both lofty EPS expectations as well as PE multiples, something David Tepper warned about back in August before the ETFlash crash.

Then again, perhaps not, because remember: once the Fed abort the rate hike cycle as it will certainly have to, and relents (with or without an accompanying stock crash) that QE4 and NIRP are next, then we merely go back to square one, where the market levitates courtesy of direct Fed intervention and the cycle begins from scratch. At that point there will be only one question left: does the Fed have enough credibility left to herd the various market algos into levitating asset prices for yet another QE season, or will that be it?

Leave A Comment