Last week I had the pleasure of attending Evercore ISI’s Energy Policy & Geopolitics Conference in Washington, D.C., where I visited with senior staff responsible for infrastructure and energy decision-making. The meetings were encouraging and highly instructive, and they opened my eyes up to some of the lesser-known inner workings of the government.

Among them is the reconciliation process, whereby Congress instructs a number of committees to report on any budgetary changes a new bill or spending package might trigger. For example, if President Donald Trump truly wishes to build a wall on the southern border, he’ll need to acquire the capital from other areas of the government’s budget. In other words, “the wall” must turn out to be revenue- and distribution-neutral. It’s a highly complex process—all matters of policy are entwined in and affect various departments, after all—which partly explains why Congress often seems to have such difficulty getting anything accomplished, including repealing Obamacare.

As President Donald Trump admitted to Reuters last week: “[Governing] is more work than in my previous life. I thought it would be easier.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), part of the reconciliation process, is one such entity that’s notorious for standing in the way of infrastructure and energy projects. The agency has traditionally held the attitude that the best development is no development. However, the Trump administration has an ace up its sleeve: the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, signed into law in December 2015. According to the official website, FAST-41, as it’s known, “was designed to improve the timeliness, predictability and transparency of the Federal environmental review and authorization process for covered infrastructure projects.” Project delays, therefore, can be combated with transparency and accountability.

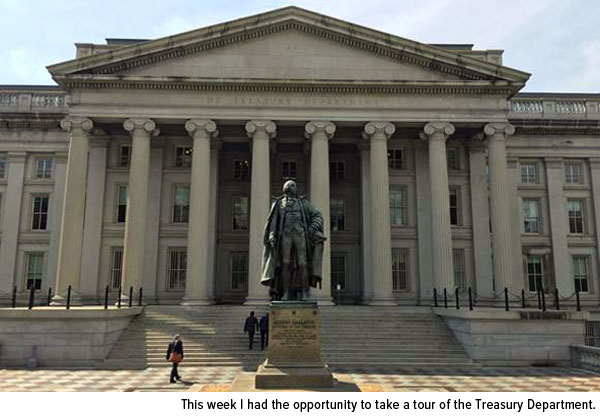

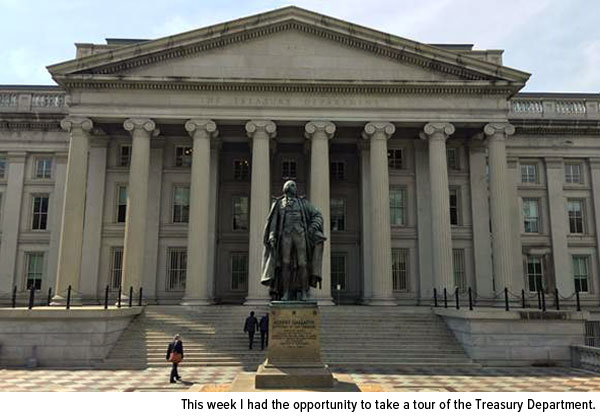

I also had the opportunity to visit the Treasury Department. I was pleased to hear that its senior analyst, who reports directly to Secretary Steven Mnuchin, closely monitors the purchasing manager’s index (PMI) and China, as we do, and keeps an eye on both oil and gold, which the department views as a currency. He seemed genuinely concerned about how federal rules and regulations might affect the work of professional brokers and traders. Specifically, he worries about impairing liquidity in capital markets, which makes price discovery exceedingly challenging. Having served in both the Obama and Trump administrations, the analyst was very insightful, articulate and balanced in his views. Not once did he have an explicitly negative thing to say about either president, and I got the sense that he cared deeply about the execution of his job, which was highly encouraging.

Leave A Comment