The rationale for today’s easy money policies is pretty straightforward: Falling interest rates and rising government deficits will counteract the drag of excessive debts taken on in previous stimulus programs and asset bubbles, enabling the developed world to create wealth faster than it takes on new debt. The result: a steady decline in debt/GDP to levels that allow the current system to survive without wrenching changes.

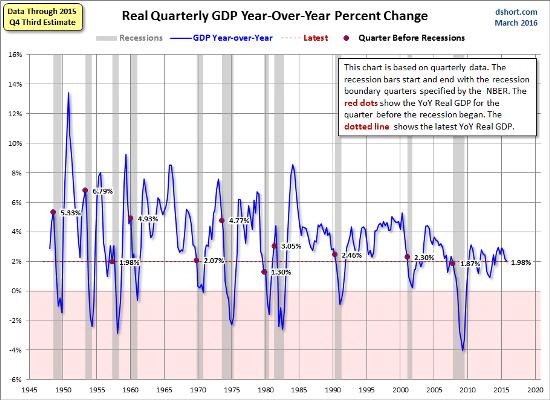

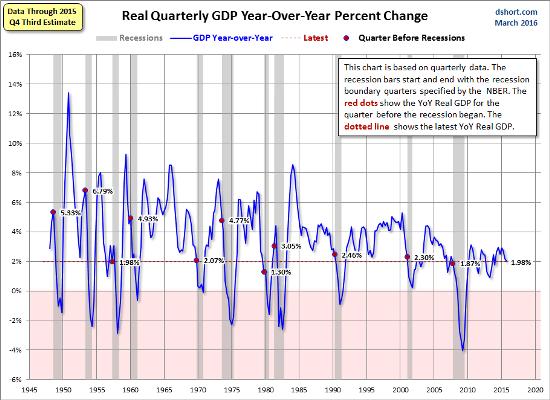

That’s a seductive, free-lunchy kind of idea — if it actually worked. But as the following chart of historical US GDP growth illustrates, as we’ve taken on more and more debt, each successive stimulus program has generated less and less growth. Compare the past few years to the rip-roaring recoveries of the 1960s through 1990s and it’s clear that whatever mechanism once converted easy money into greater wealth is no longer operating.

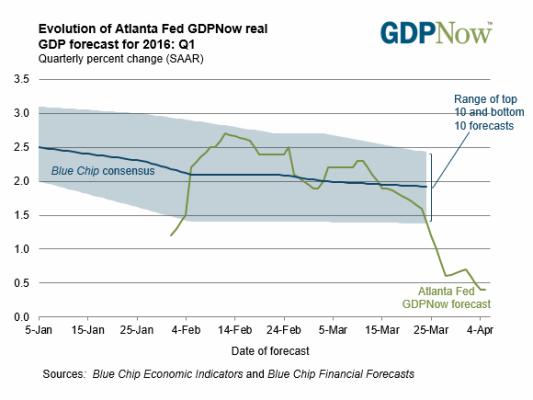

And note that the 2% recent growth on the above chart doesn’t include the revision of Q4 2015 growth to only 1.4%, and the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow projection of 0.4% growth for 2016’s first quarter.

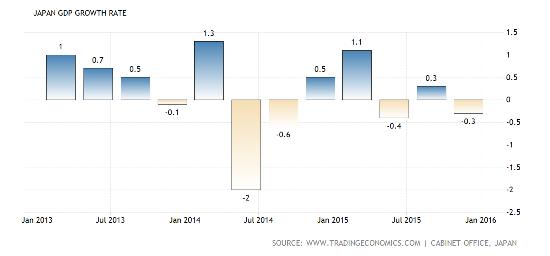

It’s the same story pretty much everywhere else. Japan, for instance:

Now the question becomes, how does the US and the rest of the world “grow out of its debt” if it can’t grow at all? Won’t the steady accretion of debt at every level of every society go parabolic in a zero-growth world? The answer is that mathematically speaking, this appears to be unavoidable.

So what will we do? More of the same of course:

OECD Calls for Urgent Increase in Government Spending

(Wall Street Journal) – Governments in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere should take urgent and collective steps to raise their investment spending and deliver a fresh boost to flagging economic growth, the Organization for Economic Growth and Development said Thursday.

In its most forceful call to action since the financial crisis, the OECD said the global economy was suffering from a weakness of demand that couldn’t be remedied through stimulus from central banks alone.

Releasing its first economic forecasts of 2016, it urged governments able to borrow at very low interest rates to boost spending on infrastructure. The OECD said that if governments worked together, fresh borrowing could have such a positive impact on growth that it would reduce rather than increase their debts relative to economic output.

OECD chief economist Catherine Mann told The Wall Street Journal that without such action, governments wouldn’t be able to honor their pledges to deliver a better life for young people, adequate pensions and health care for the elderly, and the returns anticipated by investors.

“The economic performance generated by today’s set of policies is insufficient to make good on these commitments,” Ms. Mann said, who has worked at the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Council of Economic Advisers. “Those commitments will not be met unless there is a change in policy stance.”

“Governments in many countries are currently able to borrow for long periods at very low interest rates, increasing fiscal space,” the OECD said. “Many countries have room for fiscal expansion to strengthen demand. This should focus on policies with strong short-run benefits and that also contribute to long-term growth. A commitment to raising public investment collectively would boost demand while remaining on a fiscally sustainable path.”

Leave A Comment