The Alleged Evils of “Volatility”

Whenever there is talk in the popular press or in the mainstream financial press about “heightened volatility” in the stock market, it is a euphemism for “the sucker is going down!”. Naturally, with most market participants positioned for rising prices, especially when said prices are in nosebleed territory (stocks are always at their most popular when their valuations are nothing short of crazy), nobody likes that to happen – or let us rather say, only a small minority would welcome it.

This minority consists essentially of the following people: those who believe the market is overvalued and are either shorting it in the hope of profiting from a reversion to the other extreme (“mean reversion” is relatively rare in financial markets), or those who cannot bring themselves to invest in an overvalued market and are patiently waiting for the same event in order to be able to justify buying.

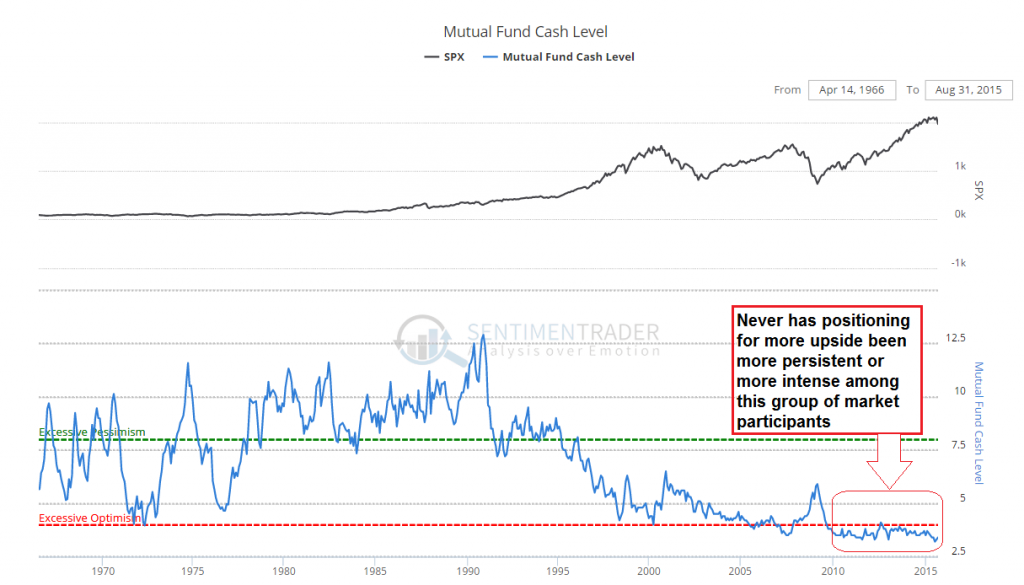

A chart demonstrating how persistent and intense the positioning for more upside is among mutual fund managers nowadays. While this is only one of the groups active in the market, it is probably a useful microcosm of general sentiment – click to enlarge.

The above explains why there is generally so little complaint about prices being distorted as long as it’s to the upside. However, when titles to capital are rising at a faster pace than other prices in the economy, it can only be for two possible reasons: the first is that people are saving more, in order to be able to consume more in the future. This is an expression of declining time preferences and lowers interest rates; this in turn will be reflected in rising prices for capital goods – the more distant from the consumption stage they are, the bigger the effect. Titles to capital will reflect that.

The other reason is that commercial banks, the central bank or more likely both are creating more money from thin air with the express purpose of lowering gross market interest rates artificially, thereby creating an unsound boom (while at the same time depressing the purchasing power of money over time, which explains the long-run upward tendency of asset prices). Obviously this is what has been happening most of the time since central banks have been around, and it has happened to an even greater extent since the monetary system has become a pure fiat money system, in which irredeemable money can be issued in any old quantity.

Since the latter method is so well entrenched, artificially distorted prices have become the “new normal”. The booms are much bigger and lengthier than they would otherwise be, and the amplitude of the busts is accordingly greater as well. Incidentally, the last bust has scared central bankers so much, that they are now eagerly working on creating the preconditions for a bust that will eventually put its immediate predecessor in the shade.

Anyway, one of the effects of this is that market participants, after bidding up prices to ever more dizzying heights for a while, have a tendency to discover the fact that they are unsustainable rather suddenly, in herd-like fashion. The repricing process from unsustainable, completely distorted prices to more realistic (i.e., lower) prices thus tends to happen faster than the preceding upside distortion process – et voila, “volatility”.

Leave A Comment