Remember all the hullabaloo back in September about the Federal Reserve’s decision to shrink their balance sheet? Believe it or not, it was somewhat of a big deal and many strategists were warning about the lack of support for risk markets from this action.

Here is the actual announcement from the FOMC’s press release:

Effective in October 2017, the Committee directs the Desk to roll over at auction the amount of principal payments from the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities maturing during each calendar month that exceeds $6 billion, and to reinvest in agency mortgage-backed securities the amount of principal payments from the Federal Reserve’s holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities received during each calendar month that exceeds $4 billion. Small deviations from these amounts for operational reasons are acceptable.

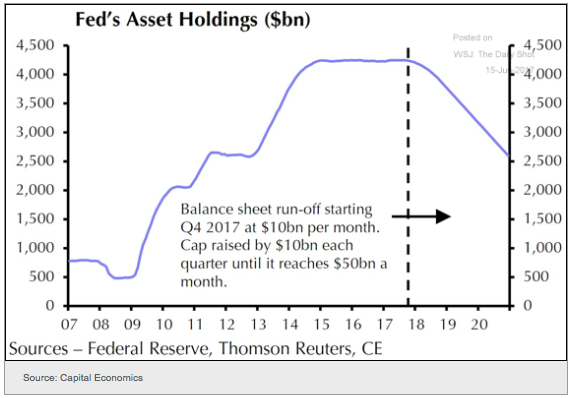

At the time I wasn’t too fussed about the action as reducing a $4.4 trillion balance sheet by $10 billion a month didn’t seem all that important.

But $10 billion is just a start. The Fed’s goal is to eventually reach $50 billion a month, with the program ending in 2020 having hopefully shrunk the balance sheet to $3 trillion.

Now as Jim Bianco likes to remind his readers, no modern economy has successfully retracted their quantitative easing program and significantly reduced their balance sheet, so if the Fed actually follows through with their plan, it will be a first.

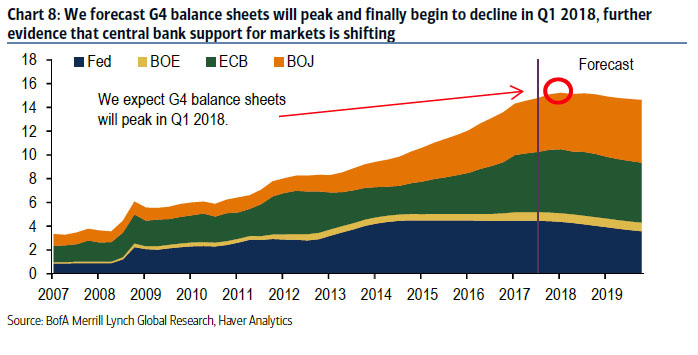

There’s all sort of hope that both the ECB and the BoJ, will also reduce their balance sheet expansion in the coming quarters. So on a net basis, global Central Banks will go from stimulating through net quantitative easing, to quantitative tightening.

Here is a chart from BofA Merrill Lynch that predicts G4 Central Bank balance sheet expansion will peak in the 1st quarter of 2018 and then gradually shrink.

Now you might believe this is a good thing, and shouldn’t affect risk markets. In fact, you might even argue that Central Bank quantitative easing is sending the wrong signal to private sector participants, and its removal will allow the economy to grow on its own naturally. That might be the case, and for those of that persuasion, you can probably stop reading now.

I don’t believe that for one second. Although the US economy is finally standing on its own, there is no doubt in my mind that quantitative easing goosed risk assets higher in the years following the Great Financial Crisis. I still remember the initial days of quantitative easing. I would start trading and then mid-morning the stock market would get a strange bid out of nowhere. For a while I couldn’t figure out why it occurred some days and not others. Eventually, I got the Federal Reserve’s Permanent Open Market Operations schedule (POMO) and noticed a direct stock market outperformance on the days when the Fed was injecting liquidity into the system through bond purchases. I don’t know how it was so direct, but after watching and analyzing the data myself, I am 100% convinced that the Fed’s POMO gave a considerable lift to risk assets.

Leave A Comment