“Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve. But I am the opposite of a stage magician. He gives you the illusion that has the appearance of truth. I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.”

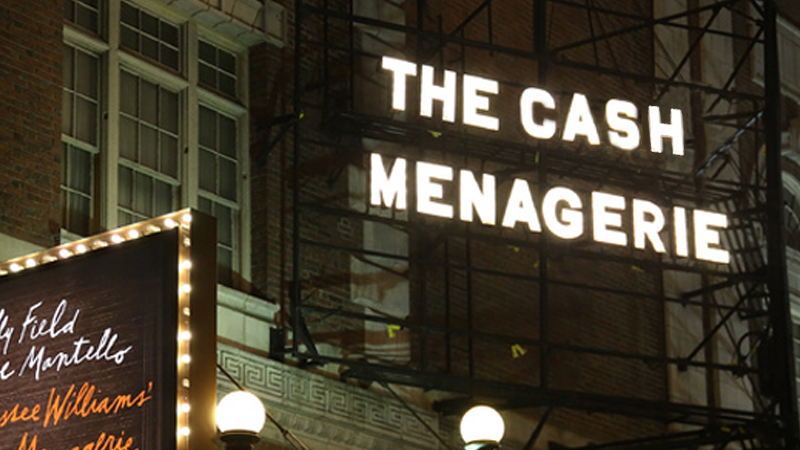

The next time you happen to find yourself at 111 West 44th Street in New York’s theater district, make it a point to gaze up at the haunting image of the illuminated sign for The Glass Menagerie, the play that launched the career of America’s greatest playwright. Maybe you too will recall the unsettling opening lines written in 1944 by Tennessee Williams, spoken by his protagonist, Tom Wingfield. Tom’s words promised to deliver the sort of truths few of us covet, though the play’s entertainment value has clearly withstood the test of time.

If you’re of the rip-the-Band-aid-off philosophy on facing life’s unpleasant realities, pivot on your heel and look across the street, to 110 West 44th Street. Your eyes will be immediately drawn to the less mesmerizing, but equally inescapable, signage gracing the edifice of that building, the U.S. debt clock, that live, unrelenting tally that is marching towards $20 trillion, be we all damned.

One must wonder if Broadway’s denizens see the theater in having these two facades stare one another down, as if taunting the other to wax more fatalistic.

This week, Federal Reserve policymakers will release a policy statement that paints an illusion of prosperity in cold monetarist verbiage that feigns the appearance of truth. The doves’ message will be uncharacteristically hawkish. They will flap their wings about accelerating underlying growth and inflation. They will allude to the time being upon us to normalize interest rates, to come in from a long, brutal winter of artifice.

The truth, you ask? Unconventional monetary policy in the form of zero interest rates and quantitative easing braced an economy that has been and remains fragile. And yet, as evidenced by the most recent bout of euphoria, animal spirits are out in full force.

There are other calendar years ending in the number ‘7’ associated with rampant speculation in asset markets and a strong Fed. Only one of the two proved to be a buying opportunity. The other stands as testament to one of the greatest monetary policy blunders in history.

Leave A Comment