“By any measure, real long-term interest rates are much too low and therefore unsustainable. When they move higher they are likely to move reasonably fast. We are experiencing a bubble, not in stock prices but in bond prices. This is not discounted in the marketplace. The real problem is that when the bond-market bubble collapses, long-term interest rates will rise.” – Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan says bonds are in a bubble.

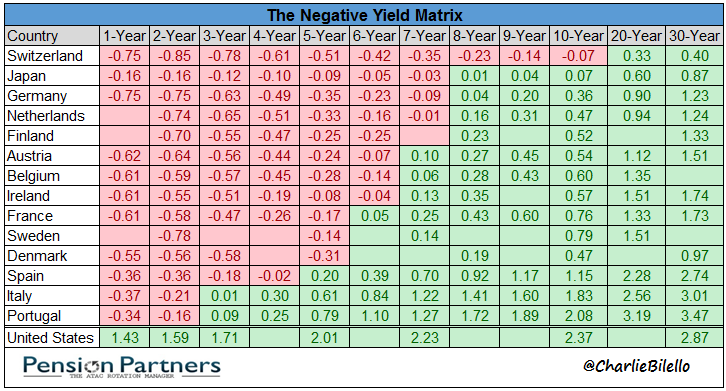

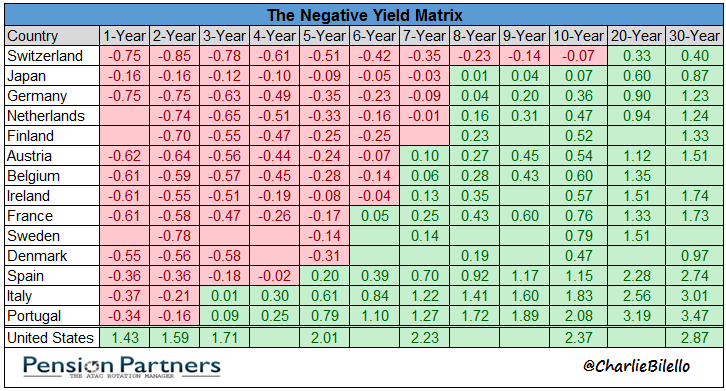

With negative interest rates across Europe and in Japan, it’s hard to argue with him.

But what exactly does it mean to say bonds are in a bubble? Are investors in a broad bond index fund going to experience a similar fate as tech investors back in 2000 (>80% losses)?

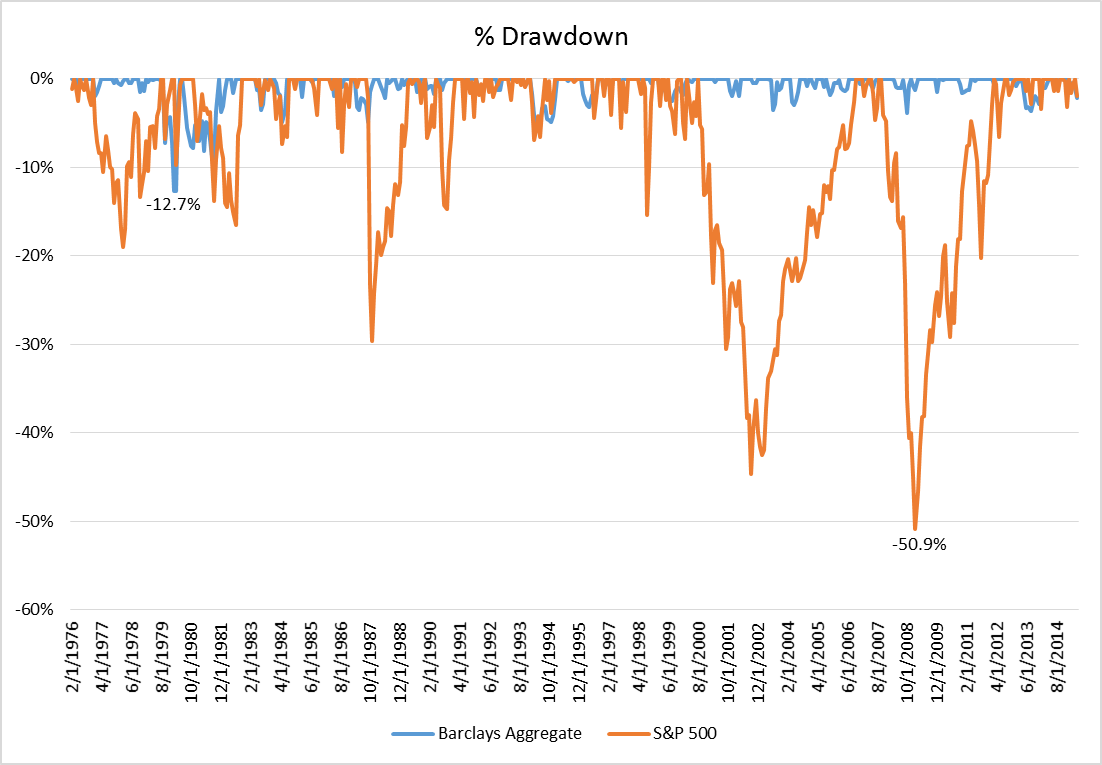

Not likely. Bonds are a completely different animal than stocks. While losses can occur during periods of rising rates, they pale in comparison to equity market declines.

Going back to 1976, the worst drawdown for the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index was 12.7% (versus over 50% for U.S. equities). This occurred from August 1979 to March 1980 when yields moved from 9.5% up to 14.1%.

The drawdown didn’t last very long. By May 1980, bonds were at new highs, and investors never saw a negative calendar year return at the time.

How is that possible? Yields were so high in the late 1970’s that the coupon payments outweighed the losses from rising rates. (Bond Math note: the higher the starting yield, the lower the duration (sensitivity to rising rates) and vice versa).

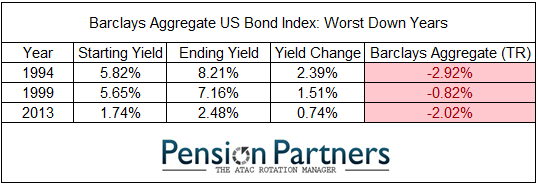

In 1994 when yields moved from 5.8% up to 8.2%, there was less cushion in terms of coupon payments. The result was a 2.9% loss for the year. A more extreme example can be seen in 2013, as it only took a minor rise in yields (1.7% to 2.5%) to bring about a 2% loss on the year.

Where does that leave us today? In a similar place to where we were five years ago: a precarious position.

Leave A Comment