When the Fed effectively telegraphed its new reaction function last month, the FOMC served notice to the world that it was not only acutely aware of what’s going on in emerging markets, but also extremely worried about the possibility that hiking rates could end up triggering something far worse than the “tantrum” that unfolded across EM in 2013.

The dire scenario facing the world’s emerging economies has by now been well documented.

In short, slumping commodity prices, depressed raw materials demand from the Chinese growth engine, a slowdown in global trade, and a loss of competitiveness thanks to the yuan devaluation have conspired with a number of idiosyncratic, country-specific political risk factors to wreak havoc on EM FX and put an immense amount of pressure of the accumulated stash of USD-denominated reserves.

For the Fed, this presents a serious problem. Hiking rates has the potential to accelerate EM capital outflows and yet not hiking rates does too. That is, a soaring dollar will obviously ratchet up the pressure on EM FX but then again, because the uncertainty the FOMC fosters by continuing to delay liftoff contributes to a gradual capital outflow, not hiking rates endangers EM as well.

As we’ve been keen to point out, DM central banks aren’t operating in a vacuum. That is, if a policy “mistake” serves to tip EM over the edge, the crisis will feed back into the world’s advanced economies forcing DM central banks to immediately recant any and all hawkishness. For more evidence of EM fragility and the link between an emerging market meltdown and DM stability, we go to FT:

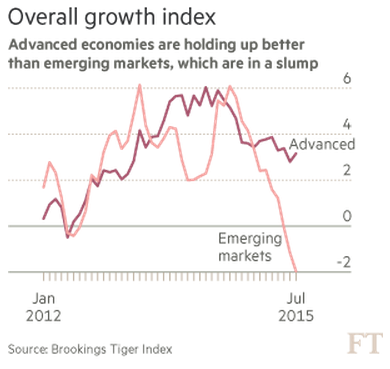

Emerging economies risk “leading the world economy into a slump”, with lower growth and a rout in financial markets, according to the latest Brookings Institution-Financial Times tracking index.

Released ahead of the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Lima, Peru, the index paints a much more pessimistic outlook than the fund is likely to predict later this week.

According to Eswar Prasad of Brookings, weak economic data across most poorer economies has created “a dangerous combination of divergent growth patterns, deficient demand, and deflationary risks”.

The Tiger index — Tracking Indices for the Global Economic Recovery — shows how measures of real activity, financial markets and investor confidence compare with their historical averages in the global economy and within each country.

The extreme weakness in the emerging market component of the Tiger growth index shows that data releases have been significantly weaker than their historic averages.

Divergence is almost as important as a new trend highlighted in the index, however, with India emerging as a bright spot and commodity importers such as Brazil and Russia mired in recession.

Because emerging economies are now much more important in the global economy and growth rates are still higher than their developed counterparts, global growth is still hovering around 3 per cent, close to its long-term average.

The concern, according to Mr Prasad is that the slump in emerging economies’ confidence will infect advanced economist in the months ahead.

Leave A Comment