Having established the farcical nature of wage interpretations on the shortest time scale, a wider contextual framework leads in the same direction of doubt. The point of any interest rate hike for monetary policymakers is to head off “inflation” before it gets out of hand; the economy “overheating.” Having undertaken sufficient (it is assumed) stimulus to surpass whatever hysteresis calculations, putting the economy on course toward more “inflationary circumstances” (sustained growth), the monetary job turns to restraint in order to ensure that once inflation starts it doesn’t go past 2% (or if it does, not for long).

With the Phillips Curve remaining somehow as the basis for policy analyses, wages and the idea of “full employment” are the general guidelines. By the count of the unemployment rate alone, full employment seems indicated; all that is left is wage growth to corroborate. For economists believing in this kind of control and controlling variables, the emphasis on, and scrutiny of, wages particularly with all the other negativity is intense. They keep saying that they “see signs” that wages are accelerating but consumer spending and the manufacturing sector (perhaps now services, too) keep moving in the opposite.

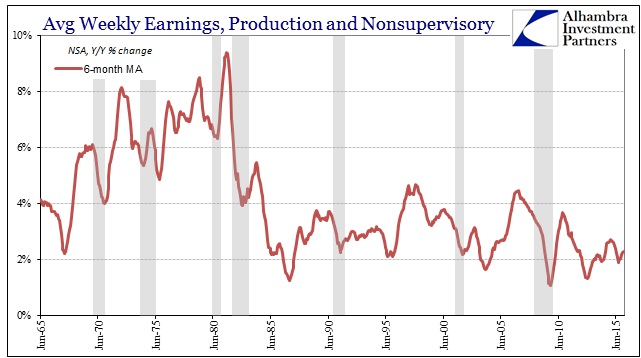

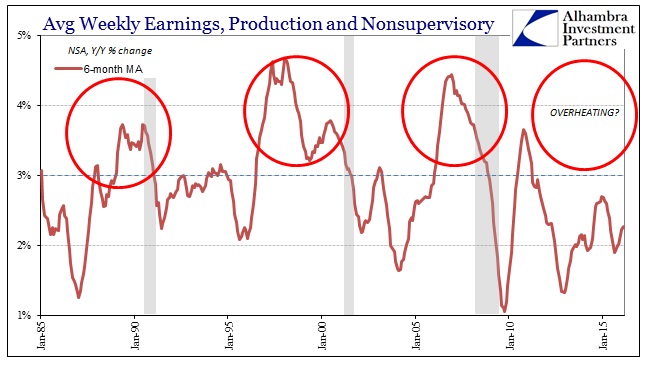

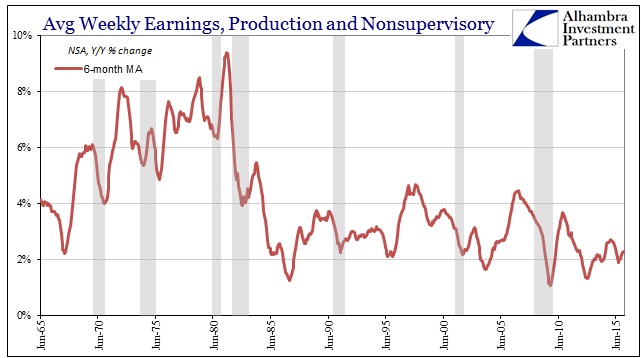

By any reasonable interpretation, earned income just isn’t there (and the above includes not just growth in wage rates but also hours to capture total earnings growth which should be quite robust at “full employment”). In fact, the longer historical perspective above downplays the dearth of income growth that we see right now.

At each of the last three cycle peaks, that is those where the unemployment rate suggested “full employment”, earnings growth wasconsistently better than 3.5%; we have not seen even 3% since the early days of the recovery right after the absolute bottom in job cutting (2010). February’s earnings growth was just 2.0%.

Leave A Comment