Japan is hot, really hot. Stocks are up to level not seen since 1996 (Nikkei 225). Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called snap elections in Parliament to secure a supermajority and it worked. Things seem to be sparkling all over the place, with the arrow pointing up:

“Hopes for a global economic recovery and US shares’ strength are making fund managers generous on Japanese stocks,” said Chihiro Ohta, general manager of investment research at SMBC Nikko Securities.

Only that isn’t real, just like it wasn’t three or seven years ago. Emotions don’t seem to be tracking well with reality, and in Japan it is no different. There isn’t even much of lingering popular belief in QQE to at least give these broad feelings the appearance of substance; global growth is coming because, well, it just has to, right?

Like here, or anywhere for that matter, stocks are up but the economy is not. Belief still clings to what is always over the horizon. You would think given the breathless coverage in the worldwide media that Japan is utterly booming, jumping with so much activity the island can’t contain it all. It just isn’t true, the story being wildly distorted as always to fit the (technocrat friendly) narrative.

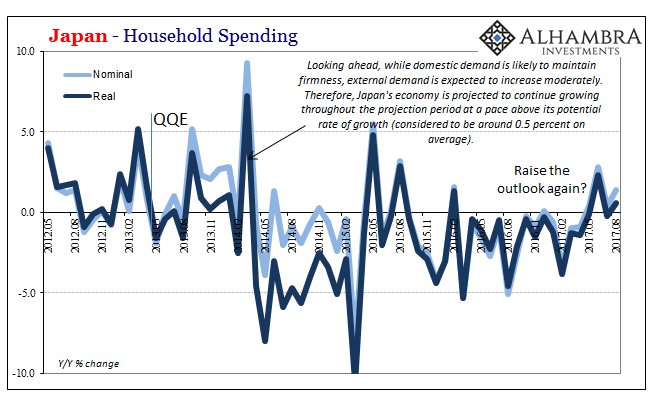

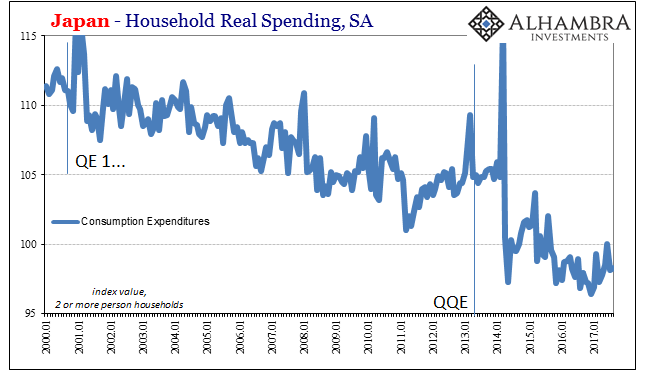

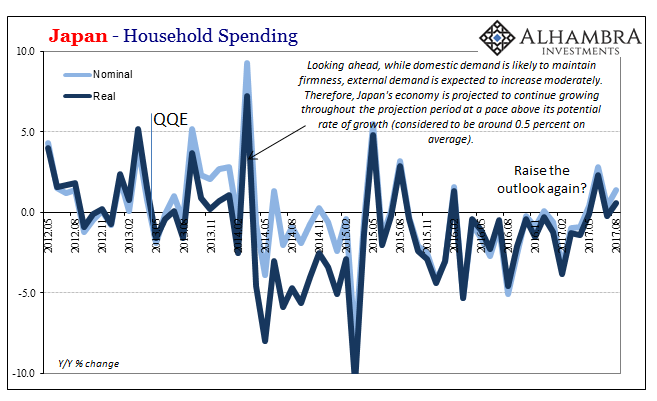

Household spending in Japan, for example, has turned slightly positive in the past few months. It sounds like more than it is, less of a positive than in the middle of 2015 when all the same things were being said about the subject by the same people. Like anywhere else, even the Japanese economy is prone to the occasional upturn. What really matters is that those brief moments of positive never come close to making up for the more widespread and sustained negatives.

It’s another relative change that is mistaken, quite often intentionally, for a categorical one. In other words, Japan is experiencing little more than a reprieve from continued contraction rather than any actual turn toward actual growth.

Leave A Comment