Last week’s forecast of “rapidly rising risk” of a global recession from Citigroup’s chief global economist, William Buiter, is attracting attention, which isn’t surprising at a time of stumbling financial and commodity markets. “The most likely scenario (40% probability), in our view, for the next few years is that global real GDP growth at market exchange rates will decline steadily from here on and reach or fall below 2% around the middle of 2016,” he wrote. “Growth is likely to bottom out in 2017 and start recovering again from late 2017 or early 2018.”

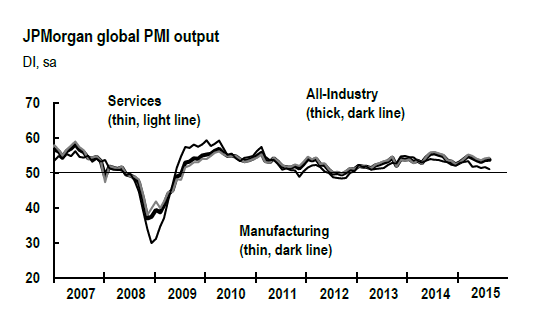

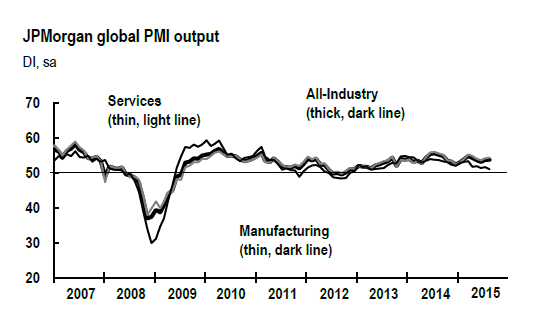

That’s a troubling outlook, although it’s still debatable if the world economy will be as weak as Buiter projects—he admits as much, as per the 40% probability estimate. Forward momentum has slowed overall, but it’s unclear if this is an issue on the margins vs. an acute problem for the global economy in general. Consider, for instance, the modestly upbeat profile of global economic activity through August, based on the latest survey data via the JP Morgan Global All-Industry Output Index. The benchmark held steady at 53.7 last month, signaling a modest rate of growth and still comfortably above the neutral 50.0 mark that separates expansion from contraction. Buiter’s forecast is effectively a warning that this index may slip closer to the neutral 50 mark if not fall below it in the months ahead.

A contraction in the future is certainly a possibility. That’s partly because of the weakness in manufacturing overall, as the JP Morgan figures show, with quite a lot of the softness concentrated in emerging markets—China, in particular.

By contrast, the services sector overall is still humming along at a relatively healthy and stable pace of growth. As such, the question is whether the global trend can turn materially weaker or negative without a substantial deterioration in services activity? Then again, are the generally upbeat numbers on services in most countries about to hit a wall? No sign of that yet.

Leave A Comment