by Costas Arkolakis and Manolis Galenianos,Vox

Greece’s trade deficit declined by 10% of GDP between 2007 and 2012, removing one of the great imbalances of the pre-Crisis years. Exports actually fell over the period, however, worsening the country’s economic crisis. This column compares Greece’s actual export performance with a benchmark for the expected trade response to the reduction in net capital. Greece’s exports should have increased by 25%, and export underperformance was responsible for a third of the country’s GDP decline. While labour markets have adjusted to the new economic environment, product markets seem to be hindering the recovery of competitiveness.

Follow up:

In 2009 it became clear that the Greek economy was facing very serious challenges arising from the country’s ‘twin deficits’ – both the budget of the Greek government and the current account of the country were in deficit by almost 15% of GDP. The two deficits required large amounts of financing that was not forthcoming in the aftermath of the Global Crisis of 2007-09, leading to the eruption of the Greek crisis. Since 2009, however, policymakers and the public have focused almost exclusively on the budget deficit. This column argues that trade adjustment (or lack thereof) constitutes a very important element of the Greek crisis.

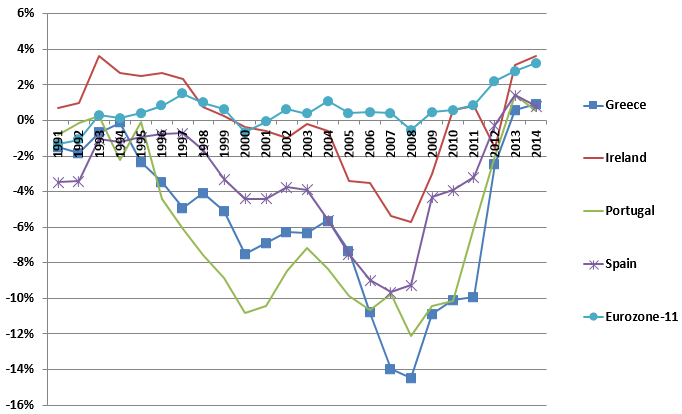

To study Greece’s trade performance, we compare developments in Greece with those in Ireland, Portugal and Spain. The comparison is informative because of these countries’ shared predicament – following the introduction of the euro, all four peripheral countries of the Eurozone experienced large net capital inflows and ever expanding current account deficits which were abruptly reversed in the aftermath of the Global Crisis (Figure 1). Furthermore, the adjustment to lower capital inflows was so disruptive that all four countries experienced severe economic crises leading to bailouts regardless of their pre-Crisis fiscal position (see Galenianos 2015 for a detailed account of the Crisis that emphasises the importance of the balance-of-payments dimension).1

Figure 1. Current account balance (% of GDP)

Rebalancing trade to an environment with low net capital inflows is the common challenge faced by all peripheral countries of the Eurozone, one which requires a combination of higher exports and lower imports. While trade balances have indeed improved dramatically and fairly uniformly across the periphery, the pattern of improvement varies considerably across countries. Portugal, Spain and especially Ireland have managed to significantly expand their exports, but Greek exports actually declined between 2007 and 2012, as shown in Figure 2 (the most recent year in our analysis is 2012 for reasons of data availability). The weak performance of exports suggests that the Greek economy has not adjusted to the new international environment.

Leave A Comment