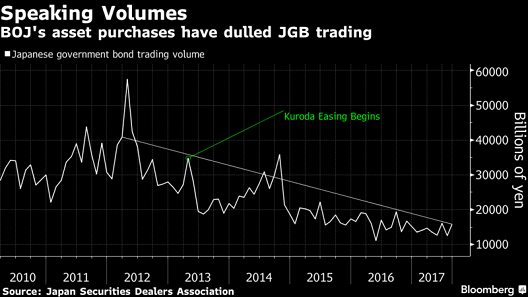

On Tuesday, market watchers did not witness the buying or selling of a single 10-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) on an exchange. Not a one.

Let that sink in for a moment. The Bank of Japan has swallowed up so much of the country’s debt obligations in its quantitative easing endeavors, trading activity across the entire JGB space has become “razor thin.”

Theoretically, the circumstances could present liquidity risk. The bid-ask spread for JGBs could widen to such an extent that investors could struggle to sell at a “market price.”

Who would consider buying in a market where you might not be able to sell? (Or short-sell in a market where you could not buy back in.)

In reality, the Bank of Japan would alleviate the liquidity issue by becoming the buyer of first, second, third and last resort. And it may have to do so. Panicky sellers could appear, fearful that the Bank of Japan will be forced into a less accommodating phase due to tightening by the Federal Reserve and tapering by the European Central Bank.

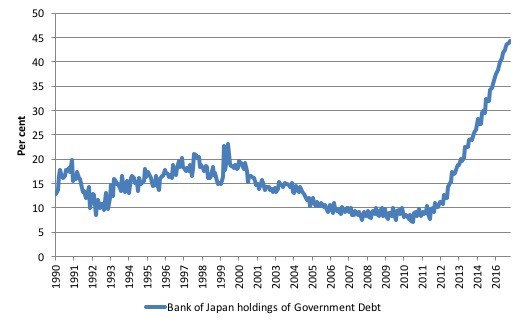

Bear in mind, the Bank of Japan already owns roughly 45% of the Japanese government bonds in existence. That number is likely to hit 60% by the end of 2018.

Will Japan eventually gobble up all of its country’s government bonds? Unfortunately, the Japanese government spends gobs of money that it does not have. Nor will the country ever receive enough in tax revenue to finance its spending needs, including the repayment of debts and any interest.

So what does the Japanese government decide? It issues new obligations at 0.1% interest and spurs its central bank, the Bank of Japan, to buy the new debts at ridiculously high prices and non-existent yields. (Nobody outside of Japan covets “IOUs” of questionable quality that yield nothing. They might as well hold cash.)

At 250% debt-to-GDP, though, 0% 10-year yields via “yield curve control” may always be necessary to continue servicing debt obligations as well as to stimulate economic growth. Permanently.

Leave A Comment