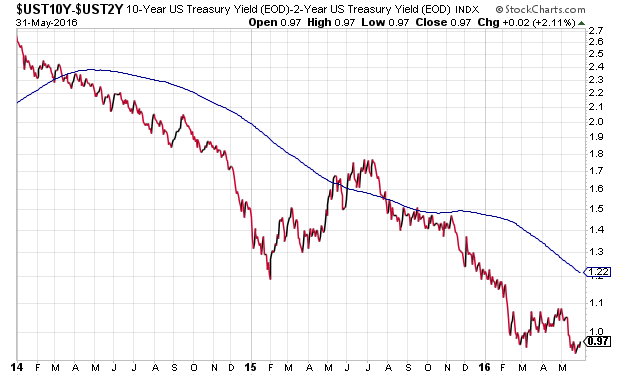

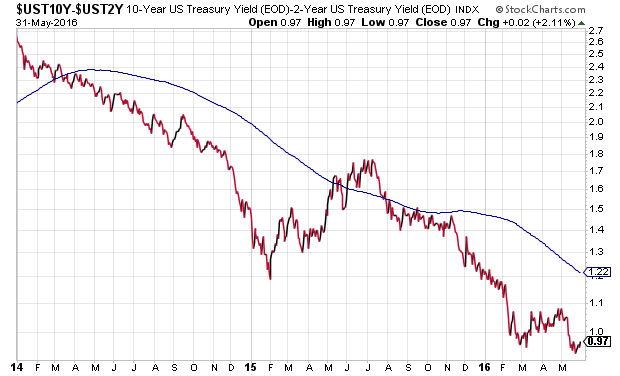

How dependent is the U.S. economy on stimulus by the central bank of the United States? Take a look at what has happened in the bond market since the Federal Reserve began to reduce asset purchases as part of its quantitative easing program (“QE3?) in 2014. The spread between longer-term maturity treasuries and shorter-term maturity treasuries has narrowed dramatically.

The two-and-a-half year downtrend demonstrates a phenomenon called “yield curve flattening.” And it is warning that the Fed’s halfhearted attempts to slowly remove economic stimulus could result in stagnation or recession.

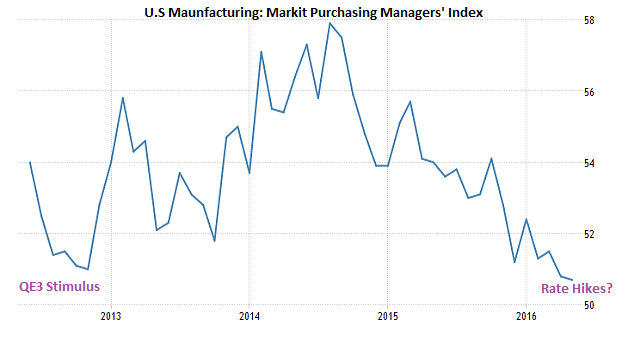

To be frank, some parts of the U.S. economy are already stagnant. Manufacturing has been free-falling for two years due to the global economic slowdown. Markit, the financial information provider, explained that the ongoing deterioration of manufacturing output is not going to bolster any warm-n-fuzzy feelings for those who might have been hoping for domestic economic resilience.

The reality on the manufacturing element of the U.S. economy is relatively straightforward. When the Federal Reserve actively expanded its balance sheet (via QE3) in its effort to ward off recessionary pressure in 2012, the U.S. economy responded favorably. During the central bank’s drawn out stimulus reduction in 2014, however, manufacturing peaked and subsequently began to weaken.

In fact, things got worse for manufacturers. The Fed eventually stopped its asset purchases altogether in the 4th quarter of 2014; it later raised its overnight lending rate by a negligible 0.25% in the 4th quarter of 2015. And now it is strongly considering another bump higher here in the summer of 2016. As modest as these “tightening” moves have been, the policy direction eventually created a lifeless environment for U.S. manufacturers, miners and gas providers.

There’s little question that the investment community has taken notice of the relationship between manufacturing and central bank stimulus removal. Yield spreads between longer-term 10-year treasury bonds and shorter-term treasury bonds chimed in at more than 2.5% at the beginning of 2014. Back then, one received 2.5% more per year in interest payments by allocating money to a 10-year maturity rather than a 2-year maturity. That was a confidence-inspiring spread in the world of U.S. sovereign debt. Today? You’re going to get less than 1% (0.97) more in interest payment for the same decision. In fact, you’re going to get roughly 1.85% annually for a 10-year, which is significantly less than the spread between “10s” and “2s” just two-and-a-half years ago.

Leave A Comment