How fast can the Canadian economy grow? What can Canadians expect now that commodity prices have plunged and the country is running a trade deficit?

These questions take on greater significance with the shift in political power to the Liberals who campaigned on growth through fiscal stimulation and government deficits. Government revenues are tied closely to a nation’s capacity to growth; higher incomes provide room to stimulate the economy without generating deficits. This blog discusses Canada’s potential and expected growth against weakened commodity prices, a slowing international economy, and accompanying deflationary pressures.

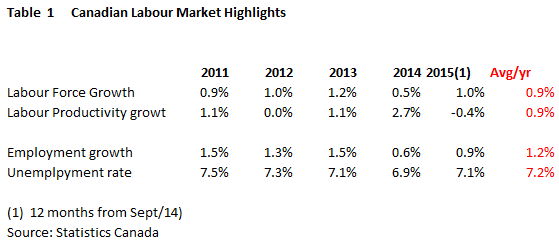

Estimating a nation’s potential GNP is simple: combine yearly changes in the labor force with yearly changes in labor productivity. More workers and greater efficiency increases potential output. The gap between potential and actual GNP growth is the unemployment rate. Falling short of potential growth results in underemployment.

What is behind Canada’s poor economic performance

Both Canadian labor force and productivity have grown by 0.9% annually. The combined growth of 1.8%, however, is insufficient to provide full employment; unemployment averaged 7.2% over the period well above conventional estimates of full employment around 5%.

Changes in the labor force are basically predetermined by demographic trends, but changes in productivity are quite variable. Capital investment and technological innovation affects the efficiency of every worker. Human capital in the form of worker skill and experience also generates greater labor efficiency.

While Canadian capital investment varies from year to year, investment has steadily declined over the past few years. The trend is for increases in capital expenditures to continue to decline, especially in the resource sector. This steady reduction in the growth of investment contributes to the mediocre labor productivity.

Leave A Comment