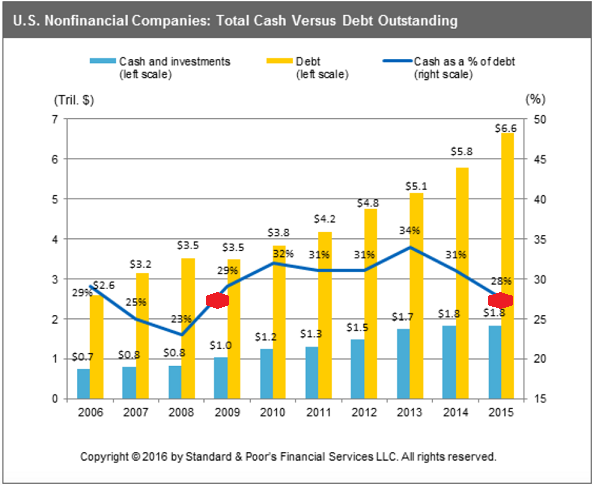

Cash on corporate balance sheets grew at a 1% pace to $1.84 billion in 2015. That’s a record level of dollars on the books. On the other hand, debt grew at a clip of nearly 14.8% to $6.6 trillion from $5.75 trillion. That’s a 15% surge in debt obligations.

In fact, American companies have grown their debt load at a double-digit annualized rate since the economic recovery began in 2009. Doing so has put corporations in a precarious situation – circumstances where cash as a percentage of debt is lower than at any time since the Great Recession.

Obviously, the data points themselves are unnerving. Yet, the trend for cash as a percentage of total debt over time may be even more alarming. Consider what transpired between 2006 and 2008. Cash growth began to slow. Debt began to skyrocket. And cash as a percentage of debt steadily declined until, eventually, stocks of corporations found themselves losing HALF of their value.

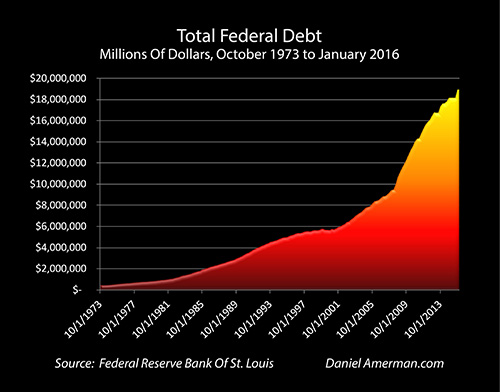

Are stocks set to log -50% bearish losses going forward? Perhaps. Perhaps not. Yet the notion that debt can perpetually grow at a double-digit rate without adverse consequences is about as inane as the idea that the U.S. government’s debt troubles are irrelevant to the country’s well-being.

At least in the U.S. government’s case, its leadership can print currency and/or manipulate borrowing costs. (Note: That is not an endorsement of policy; rather, it is an acknowledgement of government power.) Companies? They’re at the mercy of the corporate bond market such that, when existing obligations are retired, new debt may need to be issued at much higher yields to entice investors.

Think about it. Ratings companies like S&P may find themselves downgrading scores of corporate bonds to junk status due to ungodly cash-to-debt ratios. What’s more, yield-seeking investors might squeamishly back away from speculation if spreads between corporates and treasuries widen further. Additionally, Fed efforts to raise overnight lending rates may push junk yields further out on the ledge where the combination of widening spreads, rating agency downgrades and Fed policy direction collectively reinforce a negative feedback loop.

Leave A Comment