Bizarre Monetary Experiment Expanded

As is well known by now, the ECB Council has decided to expand its bizarre monetary experiment further. All users of the euro are to be subjected to additional impoverishment, by means of the ECB lengthening the duration of its outright money printing scheme (while keeping its level steady at what is an already stunning €60 billion per month) and the even more absurd decision to lower its deposit facility interest rate further, to minus 30 basis points.

ECB chief Mario Draghi, who increasingly looks like something that has risen from the Crypt. US high IQ moron export Larry Summers likes his policies. Any more questions? Photo credit: Michael Probst / AP

In much of the German-speaking press, the ECB’s deposit facility rate is rightly referred to as a “Strafzins”, which translates as “penalty interest rate”. As we have discussed in these pages at length in the past (see “The Consequences of Negative Interest Rates” as an example), if you still needed proof that our John Law-type monetary overlords are nothing short of insane, the imposition of negative interest rates is surely providing it in spades.

To briefly recapitulate: the passage of time is actually meaningful for human beings. We all differentiate between “sooner” and “later”. The natural interest rate can never become zero or negative, as this would indicate that the categories “sooner” and “later” have lost their meaning. As Mises pointed out, such an interest rate would imply a complete cessation of consumption – all our efforts would be directed toward providing for the future. We’d all starve to death.

As he remarked, a zero or negative interest rate would never emerge in an unhampered free market economy. It can only emerge because it is imposed by force by a monetary authority. This has consequences – the chief consequence is that it promotes the consumption of capital. After all, why would anyone save if they have topay borrowers instead of getting paid by them? The imposition of negative interest rates is utter economic nonsense.

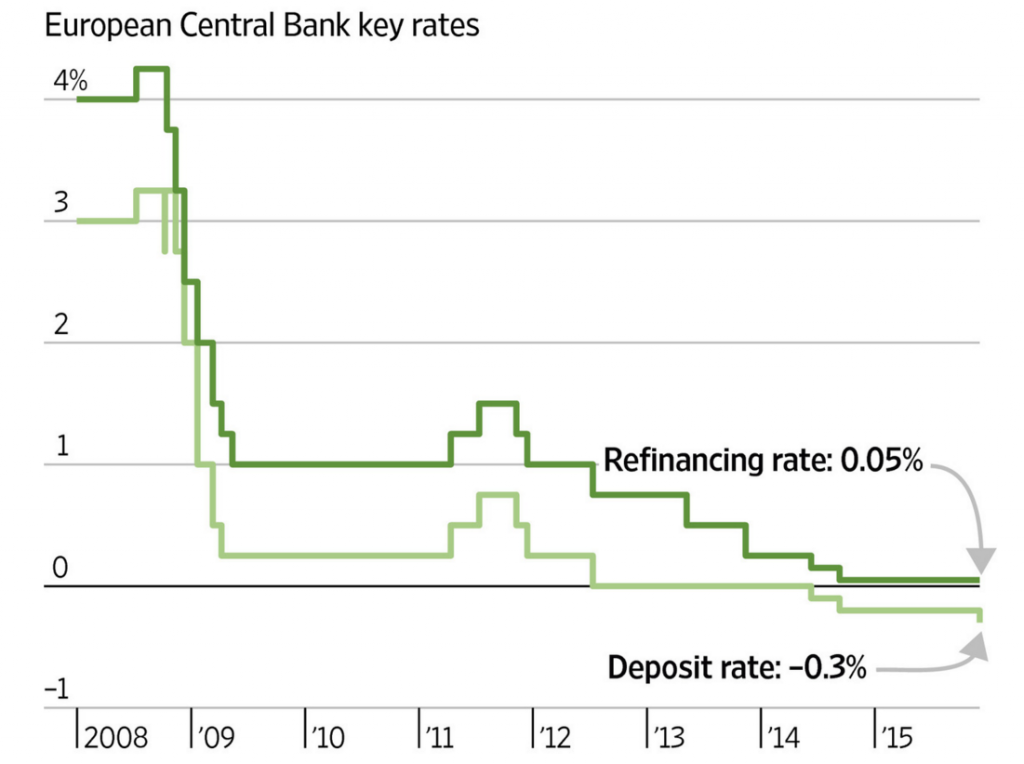

The ECB’s main refinancing rate remains stuck at 0.05% (the functional equivalent of zilch), while the deposit facility rate has been lowered further into negative territory, to minus 0.30%.

The negative rate imposed by the ECB affects only bank reserves and euro area banks have as of yet not dared to pass it on to their customers. Allegedly it is going to encourage banks to expand their inflationary lending. Even if that were the case – and so far it seems a dubious proposition, as it primarily means that banks are faced with additional costs – it makes no sense to encourage banks to create new loans and deposits if there is little credit demand and potential borrowers willing to take out loans are not considered creditworthy.

In the end, the banking system will simply be saddled with even more non-performing loans. In fact, this is already a certain long term outcome of the monetary pumping and suppression of interest rates implemented by the ECB, as the policy promotes capital malinvestment by distorting relative prices across the economy. The price for a short-lived weak recovery in aggregate economic data will eventually be an even greater economic bust. What happens then?

The ECB keeps arguing that there is “too little inflation”, because a harmonized index of consumer prices in the euro area – in other words, an index that purports to measure what is inherently immeasurable – is allegedly “too low”. Leaving aside that the so-called “general price level” is a mythical construct that does not actually exist, this “price stability” fetish is extremely dangerous. Its pursuit by the Federal Reserve in the 1920s wasthe root cause of the 1920s boom and the subsequent Great Depression.

In a free market economy, prices will generally tend to decline over time, reflecting the steady increase in productivity. They can only be kept level or be forced to rise if the money supply is continually inflated. Andthat is what inflation actually is – the expansion of the money supply. In periods during which prices tend to come under greater pressure due to either especially strong productivity growth or other exogenous reasons, the money supply expansion required to keep them “stable” will have to be especially large.

Leave A Comment